One of the main questions in exoplanet science concerns M dwarfs (red dwarfs) and the habitability of exoplanets that orbit them. These stars are known for their prolific and energetic flaring, and that's a problem. M dwarfs are so small that their habitable zones are in tight proximity to them, putting any potentially habitable planets in the direct line of fire of all this dangerous flaring.

Astronomers have been working to understand this issue, but there's no clear consensus. The issue is important because up to 70% of the stars in the Milky Way are red dwarfs, and they're known to host rocky planets. Some research shows that Earth-sized planets are the most abundant type of planet orbiting these stars.

However, red dwarfs aren't the only stars that flare. Sun-like stars do too, as anyone who follows astronomy news knows.

Our current era is marked by the development of increasingly powerful and sophisticated telescopes, both in space and here on the ground. The study of exoplanet habitability is part of the driving force for most if not all of them. Some telescopes are developed solely to find and study potentially habitable exoplanets. The ESA's PLATO space telescope will find and characterize rocky explanets in habitable zones and is due to launch this year.

But along with a larger sample and better knowledge of exoplanets, astronomers also need a better understanding of stellar flaring and M dwarf flaring in particular. A new white paper submitted to the ESO's Expanding Horizons inititative outlines how researchers can gain a better understanding of flaring. It's titled "Habitability of exoplanets orbiting flaring stars." The first author is Rebecca Szabo from the Astronomical Institute of the Czech Academy of Sciences.

In the early days of exoplanet research, astronomers found many Earth-like exoplanets in stellar habitable zones. Initially, they were attracted to M dwarfs hosting these types of planets because they evolve more slowly, meaning they have more stable and long-lived habitable zones. Over time it became clear that these stars feature prolific flaring and coronal mass ejections. That's a problem because they host so many of the known potentially habitable exoplanets.

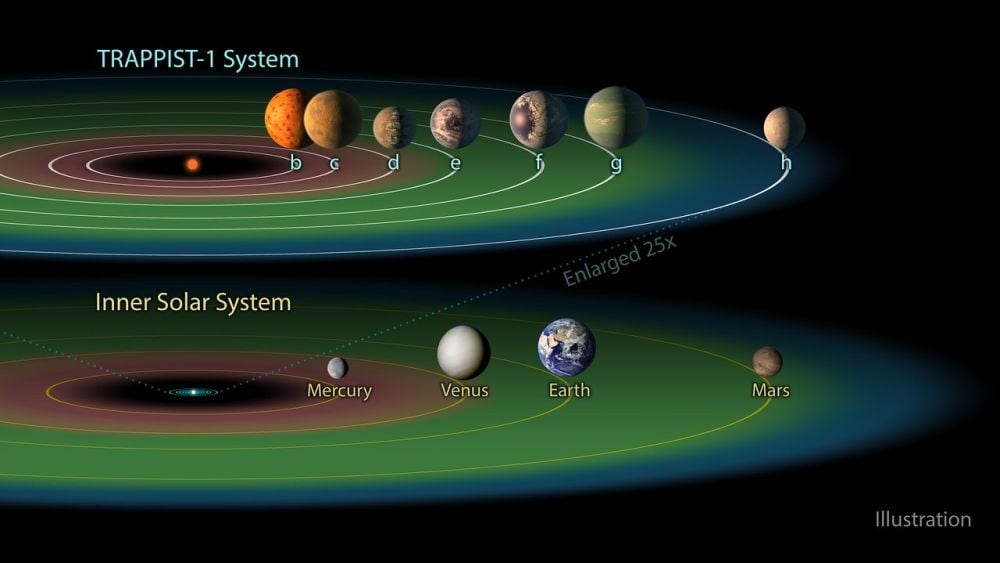

*The well-known TRAPPIST-1 system features a small red dwarf orbited by seven rocky exoplanets, each one approximately Earth-sized. Three of them may be in the habitable zone, but the question of stellar flaring may limit their habitability. Image Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech*

*The well-known TRAPPIST-1 system features a small red dwarf orbited by seven rocky exoplanets, each one approximately Earth-sized. Three of them may be in the habitable zone, but the question of stellar flaring may limit their habitability. Image Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech*

"As of late 2025 there are about 70 exoplanets that meet the formal criterion of having equilibrium temperatures allowing the presence of liquid water and about 50 of them orbit M-stars, known for their strong chromospheric activity," the authors write. Strong chromospheric activity includes flaring and coronal mass ejections (CME) that can erode atmospheres necessary for habitability. "The energy release during a typical flare is always accompanied with an emission of EUV and X-ray electromagnetic radiation, typically also accompanied by the eruption of hot solar plasma confined in a magnetic field – the coronal mass ejection," they explain.

While the Sun emits flares and CMEs, it's activity is relatively tame compared to some stars. Some stars emit superflares, which are defined as flares with 10 times more energy than the Sun's most energetic flares. Red dwarfs are known to emit these more often than other stars, though some Sun-like (G-type) stars have been observed emitting them. (The Sun has never been observed emitting one.)

"Impact of stellar activity on planetary environments and the potential for life require accurate estimates of flare energies," the authors write. "Radiation and particle outputs profoundly influence planetary atmospheres." Research from 2019 shows that high-energy flares that occure at least once per month can eliminate a planet's ozone layer. Without an ozone layer, the surface is exposed to the brunt of a star's UV energy, potentially sterilizing it completely.

Astronomers can study the Sun's activity in great detail. In fact, there are several current missions entirely dedicated to studying it, like the Parker Solar Probe and the Solar Dynamics Observatory. "On the other hand, spectroscopic information about flares on stars other than the Sun is sparse," the authors write.

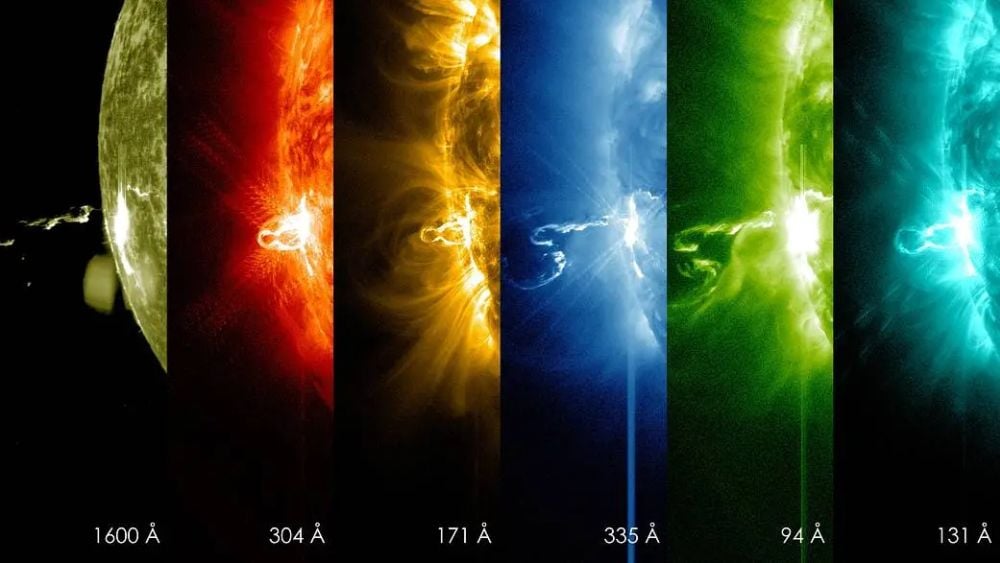

*This image shows a solar flare from the Sun in different wavelengths as imaged by the Solar Dynamics Observatory. This type of detailed observations of other stars is necessary to understand flaring and how it affects habitability on exoplanets. Image Credit: NASA/SDO*

*This image shows a solar flare from the Sun in different wavelengths as imaged by the Solar Dynamics Observatory. This type of detailed observations of other stars is necessary to understand flaring and how it affects habitability on exoplanets. Image Credit: NASA/SDO*

Stellar flares are complex and without a better understanding of them, the issue of exoplanet habitability is stalled. There are unanswered questions about flaring frequency, origins, evolution over time, and the spectrum of flare radiation. The questions populate two overarching issues.

According to the authors, researchers need a clearer picture of the power distribution and frequency of flares by stellar type and age. This can be obtained by monitoring a large number of stars over time.

Researchers also need a better understanding of the danger stellar flares pose to complex life. "This study will benefit from a collaboration with biologists working on extremophiles," the authors explain, while also pointing out that it's difficult to know what the state of that knowledge will be in 10-15 years time, and what questions will need to be asked.

To advance the study of stellar flaring, the authors detail the type of telescope needed, and the type of observations required. They point to China's Wide Field Survey Telescope as a way forward. The WFST is a 2.5 meter telescope that performs time-domain studies of things like supernovae across multiple wavelengths.

The authors explain that what's needed is a facility that combines two activities. One is "a continuous high-cadence monitoring of carefully selected late-type stars spanning the parameter space of interest," and the other consists of follow-up observations of stars that exhibit flares during the monitoring observations.

To accomplish this, their proposed telescope has several requirements. These include a primary mirror larger than 4 meters and a wide field of view of about 1 to 3 degrees. It also requires extreme multiplexity, meaning it can observe multiple targets simulataneously. The authors suggest that the telescope have 30,000 fibers, which will allow it to capture the spectra of many stars at once. This type of multiplexity can dramatically increase the speed and size of a survey.

There's more to the issue of stellar flaring and habitability than the stripping away of atmospheres. Research shows that the generation of biotic compounds also requires some amount of UV radiation. Research from 2018 stated that "We can connect the prebiotic chemistry to the stellar ultraviolet (UV) spectrum to determine whether these reactions can happen on rocky planets around other stars." Stellar flares can deliver the cumulative UV necessary for the formation of biotic compounds, but too much UV can be prohibitive.

We currently know of only a few tens of exoplanets that may have the right conditions for habitability. But an understanding of flaring is a necessity for understanding these better. By surveying a vast number of stars and their flaring activity, this future telescope should break the impasse regarding habitability and stellar flaring.

"A comprehensive study focused on properties of flaring exoplanet hosts and their activity, on a much larger scale than these few tens (soon to become hundreds) of stars with habitable planets is called for, to answer the question if such stars can harbor habitable planets," the authors explain. "The proposed Wide Field Survey telescope is well suited for this study," they conclude.