Suppose you slammed together two neutrons at near-luminous speed. The resulting collision would create a cascade of particles from protons, electrons, and neutrinos to more exotic fare. We can't predict the exact number or type of particles produced, but we do know one thing: the total charge of all the particles would be zero. This is because charge is a conserved quantity, and since the neutrons have zero total charge, their resulting particles must have the same.

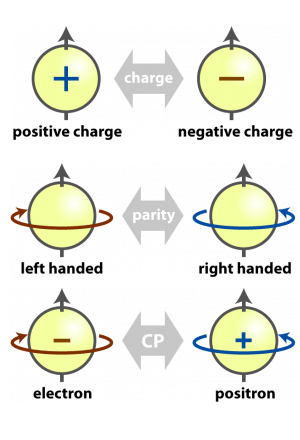

*Examples of symmetry in particle physics. Credit: Flip Tanedo*

*Examples of symmetry in particle physics. Credit: Flip Tanedo*

Electric charge (C) is just one of the inherent symmetries that governs particle physics. The others are parity (P), or handedness, and time (T). These symmetries can be combined to create CP symmetry, PT symmetry, or CPT symmetry. One consequence of this is that, when taken together, these symmetries require a symmetry between matter and antimatter. With enough energy you can create a negatively charged electron, but only if you also create a positively charged positron. Symmetry is a powerful tool in physics, but it creates a deep mystery.

The standard cosmological model says that matter was created out of the dense energy of the Big Bang. According to symmetry, matter and antimatter appeared in equal amounts, but when we look at the Universe it is made of matter. There aren't antimatter galaxies or clouds of anti-hydrogen streaming through the cosmos. Just the regular matter that makes up you and me. This mystery is known as the matter asymmetry problem.

One possible solution to this problem is to introduce an asymmetry to particle decay. It turns out that the only really crucial symmetry for cosmology is CPT symmetry. If CPT is violated, then so is Lorentz invariance, which means special and general relativity are violated, and chaos reigns. But other symmetries might be violated on rare occasions. We know, for example, that the weak force can violate CP symmetry. If PT can also be violated, then charge wouldn't be perfectly conserved. But nothing in the standard model of particle physics seems to allow for PT violation.

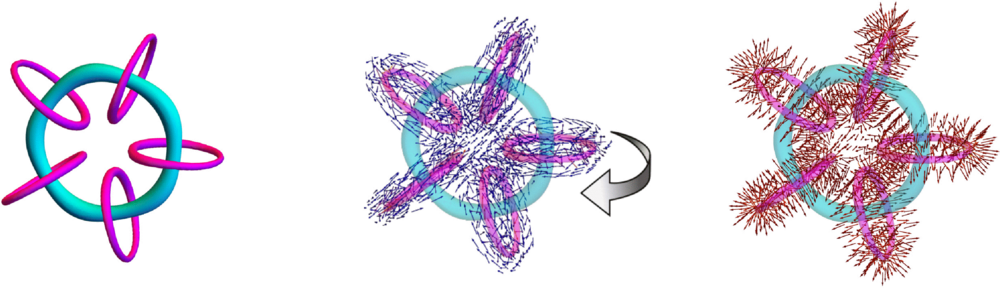

*3D plots of the numerical solution for a knot soliton. Credit: Eto, et al*

*3D plots of the numerical solution for a knot soliton. Credit: Eto, et al*

So a new work looks at an extended model of particle physics and how extended symmetries might create matter asymmetry. The authors look at two specific symmetries. The first is the Peccei-Quinn (PQ) symmetry, which is based on hypothetical particles known as axions. Axions are also often proposed as the particles of dark matter. The second is Baryon Number Minus Lepton Number (B-L) symmetry. Protons and neutrons are baryons; electrons and neutrinos are leptons. In standard physics, baryon and lepton numbers are each conserved, but some models propose the existence of heavy "sterile" neutrinos that would decay into lighter particles.

Rather than looking at specific extended models, the team focuses on symmetries and their consequences. They found that PQ and B-L symmetries allow for the formation of soliton knots within energy fields. These knots could act as a kind of pseudo-particle that would trigger an asymmetrical decay into more matter particles than antimatter ones. In other words, these knots may have formed during the earliest moments of the Big Bang, thus allowing matter to form much more readily than antimatter. The team also found that the presence of these knots in the early Universe would have left a gravitational fingerprint. In principle, a gravitational wave signal could verify the existence of these knots, though this is far beyond the current ability of gravitational wave astronomy.

While the study isn't conclusive, it's an interesting approach to the problem of matter asymmetry. Right now it's the Gordian Knot of cosmology, so perhaps it will take a new kind of knot to resolve it.

Reference: Greenberg, Oscar W. "CPT violation implies violation of Lorentz invariance." *Physical Review Letters* 89.23 (2002): 231602.

Reference: Eto, Minoru, Yu Hamada, and Muneto Nitta. "Tying knots in particle physics." *Physical review letters* 135.9 (2025): 091603.