Chemical rockets have taken us to the Moon and back, but traveling to the stars demands something more powerful. Space X’s Starship can lift extraordinary masses to orbit and send payloads throughout the Solar System using its chemical rockets but it cannot fly to nearby stars at thirty percent of light speed and land. For missions beyond our local region of space, we need something fundamentally more energetic than chemical combustion, and physics offers or in other words, antimatter.

The Apollo 11 Saturn V rocket launch vehicle lifts-off powered by chemical rocket engines (Credit : NASA)

The Apollo 11 Saturn V rocket launch vehicle lifts-off powered by chemical rocket engines (Credit : NASA)

When antimatter encounters ordinary matter, they annihilate completely, converting mass directly into energy according to Einstein's equation E=mc². That c² term is approximately 10¹⁷, an almost incomprehensibly large number. This makes antimatter roughly 1000 times more energetic than nuclear fission, the most powerful energy source currently in practical use.

As a source of energy, antimatter can potentially enable spacecraft to reach nearby stars at significant fractions of the speed of light. A detailed technical analysis by Casey Handmer, CEO of Terraform Industries, outlines how humanity could develop practical antimatter propulsion within existing spaceflight budgets, requiring breakthroughs in three critical areas; production efficiency, reliable storage systems, and engine designs that can safely harness the most energetic fuel physically possible.

The challenge lies in transforming theoretical physics into working hardware. Three major obstacles stand between us and antimatter powered spacecraft; producing sufficient quantities, storing it safely, and designing engines that can actually use it.

Current antimatter production manages thousands of atoms daily at facilities like CERN, impressive progress compared to a decade ago but roughly analogous to plutonium production capacity in late 1940’s. The process remains extraordinarily inefficient at roughly 0.000001 percent, requiring large particle accelerators and vacuum storage rings. However, recent demonstrations achieving eight times higher efficiency suggest rapid improvement is possible. A few more breakthroughs of similar magnitude could make production viable for deep space missions, where gaining extra velocity far from Earth becomes essentially priceless.

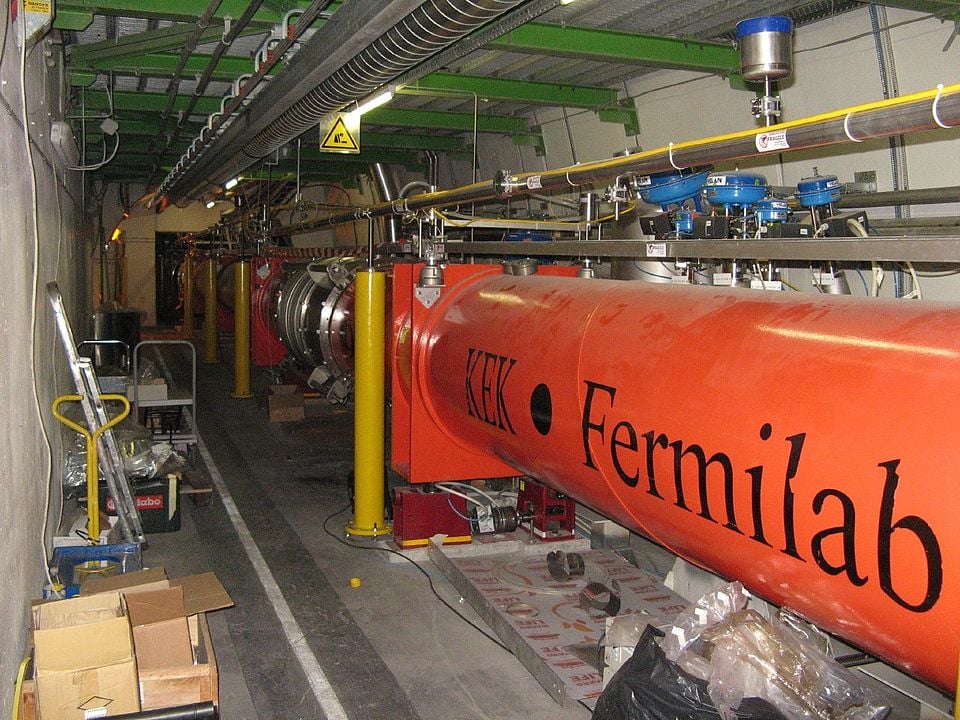

Superconducting quadrupole electromagnets are used to direct the beams to four intersection points at the Super Collider at CERN (Credit : gamsiz)

Superconducting quadrupole electromagnets are used to direct the beams to four intersection points at the Super Collider at CERN (Credit : gamsiz)

Storage presents the more challenging of these since antimatter instantly annihilates on contact with any ordinary matter. Current systems use electromagnetic storage rings to contain charged antimatter plasmas, but these are large, heavy, and delicate. A more promising approach might involve electrostatic containment, holding a tiny droplet or crystal of antihydrogen in a cryogenically cooled vacuum chamber using carefully controlled electric fields. This resembles technology already used in quantum computers and could be tested safely with regular hydrogen simply by inverting the charge.

The engine design determines whether antimatter's immense energy actually produces useful thrust. The simplest approach uses antimatter to heat a refractory block through which propellant flows, achieving performance comparable to nuclear thermal rockets without requiring an onboard reactor. More sophisticated designs combine antimatter with uranium-238, the naturally occurring form of uranium. Antiprotons can trigger fission in U-238, producing highly charged particles that deposit energy far more efficiently into the exhaust stream than gamma rays alone, enabling specific impulses anywhere from chemical rocket ranges to values suitable for interstellar missions.

The quantities required remain surprisingly modest for example, a journey to Pluto and back in under twenty years would need just 45 grams of antimatter combined with 10 kilograms of uranium-238, both occupying roughly 500 cubic centimetres of space. With chemical propulsion largely solved through reusable rockets, antimatter represents the logical next frontier for deep space exploration.

Source : Antimatter Development Program