There is a growing movement worldwide to establish a human presence in orbit, on the Moon, and beyond. This presents many challenges, ranging from the technological and logistical to the biological and medical. After all, if people are going to be living and working in space for extended periods, we need to know what the effects will be on the human mind and body. While considerable research has been conducted aboard the International Space Station (ISS), most notably NASA's Twins Study, much more remains to be done before outposts in space can be realized.

For example, there is the unresolved question of how microgravity and radiation affect lifeforms from the earliest stages of development. A team of scientists and engineers at Space Park Leicester - the University of Leicester’s hub for space research, innovation, and enterprise - has developed a new experiment involving worms. It's known as the Fluorescent Deep Space Petri-Pod (FDSPP), a miniature space laboratory for performing remotely operated biological experimentation on multiple types of organisms - including worms!

To date, the documented effects of prolonged exposure to microgravity include bone density loss and muscle atrophy, vision problems, impacts on the cardiovascular and central nervous systems, and other physiological changes. Meanwhile, prolonged radiation exposure is known to cause genetic damage and an increased risk of cancer, central nervous system degradation, and degenerative diseases. But unanswered questions remain about the effects of spending more than a year in space on living organisms (not just humans), including their aging and development.

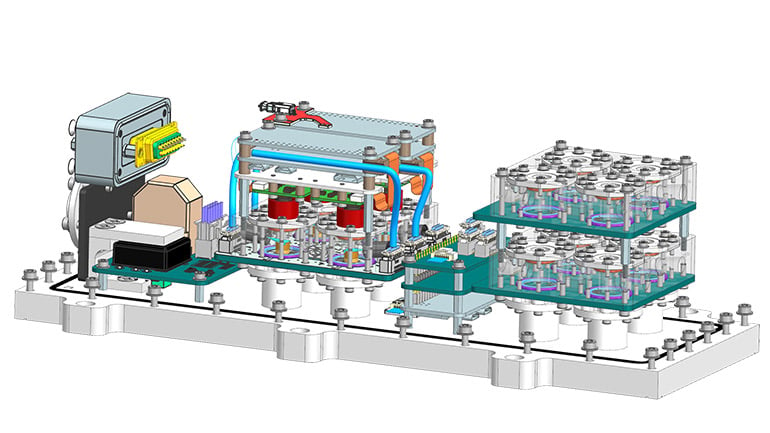

Diagram of the FDSPP experiment currently bound for the ISS. Credit: University of Leicester.

Diagram of the FDSPP experiment currently bound for the ISS. Credit: University of Leicester.

The FDSPP is a self-contained, miniaturized hardware solution for performing remotely operated biological experiments on organisms using fluorescent and white-light imaging. The experiment's development is enabled by funding from the UK Space Agency (UKSA), while launch services are provided with support from the Houston-based aerospace company Voyager Technologies. The experiment measures approximately 10x10x30 cm (~4x4x12 inches), weighs about 3 kg (6.6 lbs), and contains 12 Petri-Pods for experiments.

Each pod maintains a stable atmosphere and temperature for the organisms and provides them with all of the nutrients they need while the unit is exposed to the vacuum of space. The worms, for example, are fed and watered through an agar carrier, which is used in microbiology experiments to create Petri dishes. As Professor Mark Sims, the project manager for the FDSPP experiment at Leicester, said in a university press release:

The Fluorescent Deep Space Petri-Pod has been engineered using the electronic, engineering, software, and science expertise of the Space Park Leicester team, based around the 65-year heritage of space experiments at Leicester. This mission to the International Space Station (ISS) will demonstrate the flight readiness of FDSPP, and we believe its success will help position the UK amongst the global leaders in life sciences research for future low Earth orbit, Lunar, and Mars missions planned by Space Agencies and private companies.

The experiment will be launched to the ISS as part of a cargo flight in April 2026, carrying a crew of C. elegans nematode worms. Before the flight, the worms will have natural markers installed in their heads that respond to exposure to fluorescent stimulation. While aboard the station, these markers will allow scientists to monitor the worm's health through imaging and time-lapse video. After a short period inside the ISS, the unit will be deployed outside the station for 15 weeks to expose it to the vacuum of space, radiation, and microgravity.

The University of Leicester and Exeter teams standing with the FDRSS unit. Credit: University of Leicester.

The University of Leicester and Exeter teams standing with the FDRSS unit. Credit: University of Leicester.

The worms will occupy four pods that are regularly monitored, while the remaining eight will contain microorganisms, other test subjects, and various materials. Meanwhile, the unit will collect data on the temperature and pressure inside and outside the pods while monitoring the overall amount of radiation they absorb. This data will be relayed via the ISS downlink system and stored in the unit for download upon return. Said Professor Tim Etheridge, the principal investigator and science lead for the experiment from the University of Exeter:

Performing biology research in space comes with many challenges, but is vital to humans safely living in space. This hardware, made possible through strong collaboration between biologists around the world and engineers at Space Park Leicester, will offer scientists a new way to understand and prevent health changes in deep space on any launch vehicle.

Space biology research is also essential for developing mitigation strategies and medical treatments to address the long-term effects of spaceflight. Beyond exercise regimens routinely performed by astronauts aboard the ISS to mitigate muscle and bone loss, it is clear that medical treatments are also needed to address the impact of spaceflight on organ function, circulation, and psychological health. Such research will also help address the biggest unanswered question about living and working beyond Earth: whether children and animals can be safely born and raised in space and on other celestial bodies?

Further Reading: University of Leicester