For decades, scientists have recognized that large galaxies in our Universe have supermassive black holes (SMBHs) at their centers. These behemoths, which are millions to billions of times the mass of our Sun, play a vital role in star formation and the long-term evolution of galaxies. According to a recent study based on observations performed using NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory, it appears that most dwarf galaxies may buck this trend. This stands in stark contrast to their theory that nearly every galaxy has a massive black hole within its core.

The international team of astronomers included researchers from NASA's X-ray Astrophysics Laboratory, the Institute for Gravitation and the Cosmos, the Nevada Center for Astrophysics (NCfA), the eXtreme Gravity Institute (XGI), the Istituto Nazionale di Fisica Nucleare (IFIN), the Istituto Nazionale di Astrofisica (INAF), and multiple universities. As they describe in their paper "Central Massive Black Holes Are Not Ubiquitous in Local Low-Mass Galaxies", which recently appeared in *The Astrophysical Journal*, the team used data from over 1,600 galaxies observed by Chandra over two decades.

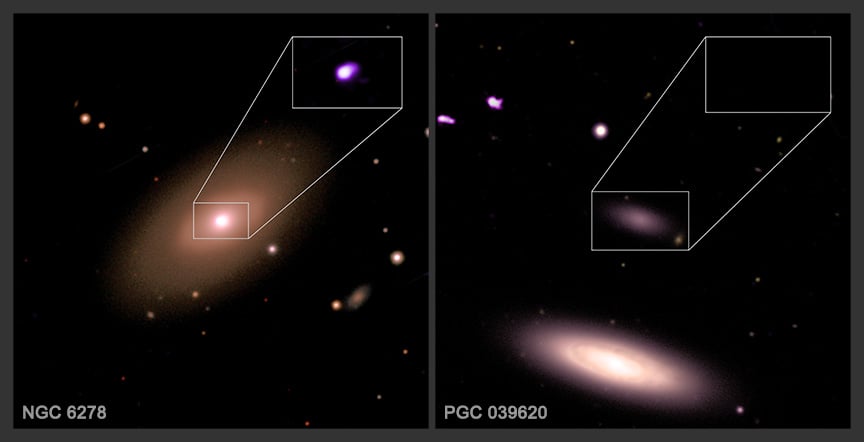

For their study, the researchers looked at galaxies ranging from a few percent of the mass of the Milky Way to those that are ten times as massive. They noted that more than 90% of the massive galaxies had bright X-ray sources at their centers, a clear indication of an SMBH. As matter falls into accretion disks around black holes, it is accelerated to speeds close to the speed of light, releasing tremendous amounts of energy across multiple wavelengths (including X-rays). When observing smaller galaxies, they found that most lacked bright X-ray sources at their centers.

*NGC 6278 and PGC 039620, labeled. Credit: NASA/CXC/SAO/F. Zou et al./SDSS/SAO/N. Wolk*

*NGC 6278 and PGC 039620, labeled. Credit: NASA/CXC/SAO/F. Zou et al./SDSS/SAO/N. Wolk*

The researchers considered two possible explanations. One was that the fraction of galaxies containing massive black holes is much lower in these less massive galaxies, while the other was that the amount of X-ray emission was too faint for Chandra to detect. The team considered both possibilities and concluded that only about 30% of dwarf galaxies likely harbor massive black holes. To reach their conclusion, the team considered how the amount of gas falling onto a black hole determines its brightness at X-ray wavelengths.

Since smaller black holes likely pull in less material, they should be fainter in X-rays and often not detectable. However, they also found that there was an X-ray deficit that could not be explained by a decrease in infalling matter. The only possible explanation for this additional deficit was that many low-mass galaxies lack SMBHs altogether. “We think, based on our analysis of the Chandra data, that there really are fewer black holes in these smaller galaxies than in their larger counterparts,” said Elena Gallo, an astronomy professor from the University of Michigan and a co-author on the study.

At present, there are two main theories on how SMBHs form. The first is the Direct Collapse Black Hole (DCBH) theory, which posits that giant gas clouds directly collapse to form black holes and would be thousands of Solar masses from the start. The other is the Stellar Collapse Seed (SCS) theory, where massive stars collapse to form black holes that then merge to form larger ones, eventually leading to SMBHs. As lead author Fan Zou of the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor explained, this black hole census could shed light on this debate:

It’s important to get an accurate black hole head count in these smaller galaxies. It’s more than just bookkeeping. Our study gives clues about how supermassive black holes are born. It also provides crucial hints about how often black hole signatures in dwarf galaxies can be found with new or future telescopes.

This study supports the DCBH theory, since the alternative would result in smaller galaxies having the same fraction of black holes are massive ones. Their results could also have important implications for the study of gravitational waves (GWs) caused by the merger of dwarf galaxies with SMBHs. A much lower number of SMBHs would mean fewer sources of GWs, as well as a much lower rate of stars being consumed by black holes. As such, the team's research offers predictions of what next-generation observatories, such as the Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA), will find when it becomes operational.

Further Reading: NASA/Chandra