Theory shows that stars can collapse directly into black holes without first exploding as supernovae. In fact, this should be a relatively common occurrence. But despite that, astronomers have found scant observational evidence to support it.

But it may have happened in our neighbour, the Andromeda Galaxy, and astronomers almost missed it.

In 2014, NASA's Near-Earth Object Wide-Field Infrared Survey Explorer (NEOWISE) observed a star in Andromeda becoming more luminous in the infrared. Those observations were contained in the data collected by the telescope and only uncovered recently. A team of astronomers were filtering NEOWISE's data for variable sources and discovered M31-2014-DS1, a supergiant star in Andromeda that appears to have collapsed directly into a black hole.

The findings are presented in research titled "Disappearance of a massive star in the Andromeda Galaxy due to formation of a black hole." It's published in the journal Science, and the lead author is Kishalay De, an astronomy professor at Columbia University.

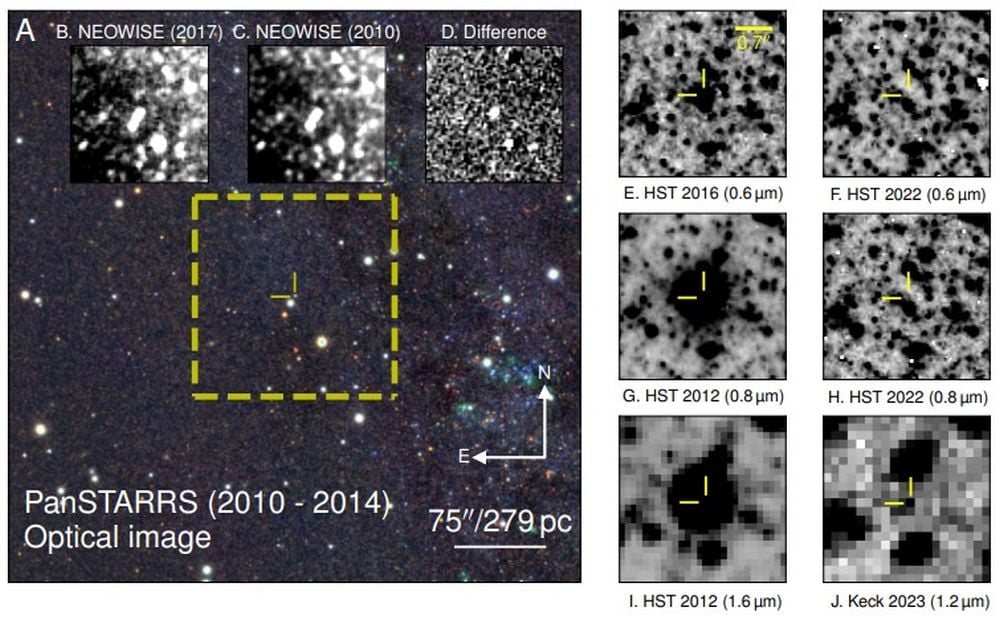

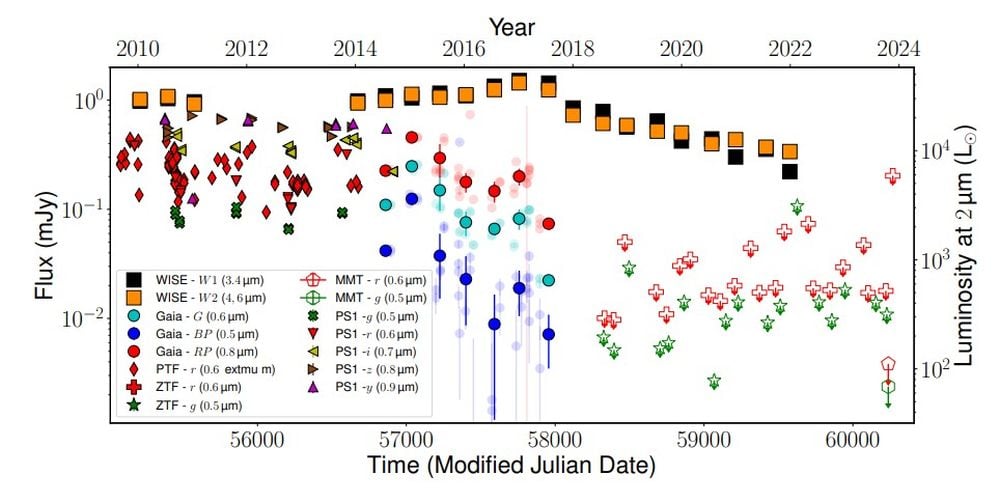

The researchers examined sequential images of M31 looking for variable sources. Images were taken every 6 months from 2009 to 2022. "Using the six-month cadenced observations from 2009 to 2022, we searched for luminous MIR transients that would accompany dusty stellar eruptions such as failed SNe," they explain. They found M31-2014-DS1, and over a two-year period beginning in 2014, the source increased its mid-infrared flux by 50%.

After two years of brightening, it faded below its initial flux in one year. The fading continued until 2022.

*This figure shows the location and disappearance of M31-2014-DS1. The main PanSTARRS image shows the object in Andromeda. The six panels on the right are from different years and show the object in different wavelengths at different times. They show the object's gradual disappearance. Image Credit: De et al. 2026. Science*

*This figure shows the location and disappearance of M31-2014-DS1. The main PanSTARRS image shows the object in Andromeda. The six panels on the right are from different years and show the object in different wavelengths at different times. They show the object's gradual disappearance. Image Credit: De et al. 2026. Science*

“This has probably been the most surprising discovery of my life,” lead author De said in a press release. “The evidence of the disappearance of the star was lying in public archival data and nobody noticed for years until we picked it out.”

The region is well-observed by other ground and space telescopes, and the researchers used those observations to retrieve optical light curves for the object. Between 2016 and 2019, its optical light faded by a factor of about 100. The object was undetectable in ground-based optical observations in 2023.

The Hubble happened to image it in 2022 and found nothing in the optical, and only a faint source in the near-infrared (NIR). Follow-up NIR observations and spectroscopy in 2023 with the Keck confirmed a faint NIR source.

*This figure presents observations from multiple telescopes over time, showing the object's dramatic fading. Image Credit: De et al. 2026. Science*

*This figure presents observations from multiple telescopes over time, showing the object's dramatic fading. Image Credit: De et al. 2026. Science*

“The dramatic and sustained fading of this star is very unusual, and suggests a supernova failed to occur, leading to the collapse of the star’s core directly into a black hole,” De said.

Whether or not a star collapses directly into a black hole without exploding as a supernova depends on neutrinos, according to the authors. When a massive star reaches the end of its life, its outward radiation can't support its own mass. The star's core collapses and releases neutrinos, and the neutrinos drive a shock wave into the star's outer layers, its stellar envelope.

If the shock is strong enough, the envelope is ejected and the star explodes as a supernova. "If the shock fails to eject it, the envelope is predicted to fall back onto the collapsing core, producing a stellar-mass black hole (BH) and causing the star to disappear," the researchers write.

The star started out with about 13 solar masses. Upon its death, it had only about 5 solar masses. It had shed most of its mass in its powerful stellar winds.

“Stars with this mass have long been assumed to always explode as supernovae,” De said. "The fact that it didn’t suggests that stars with the same mass may or may not successfully explode, possibly due to how gravity, gas pressure, and powerful shock waves interact in chaotic ways with each other inside the dying star.”

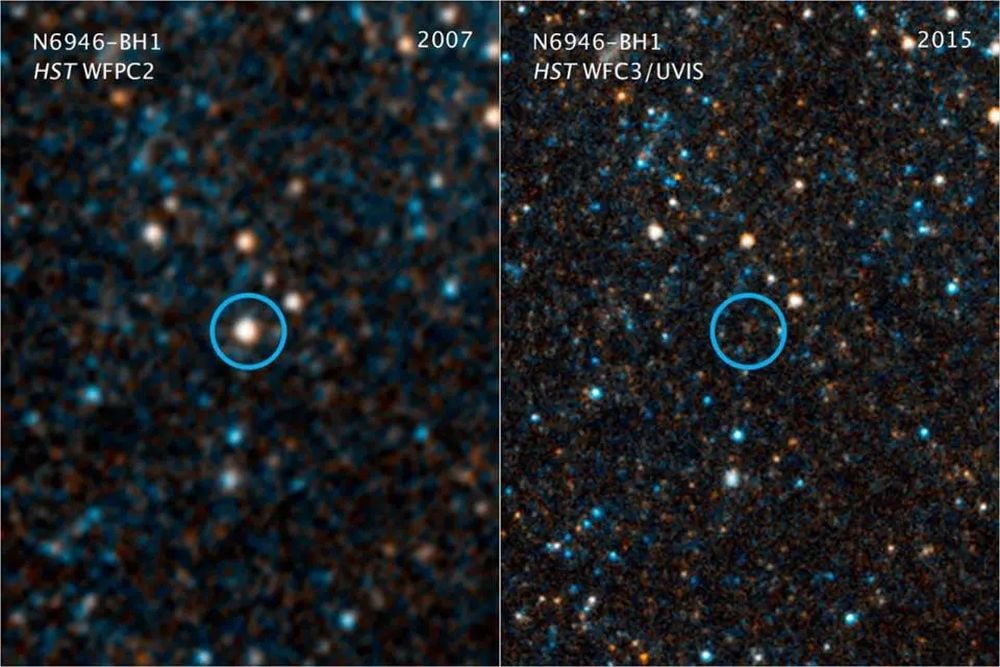

Astronomers know of one other direct collapse black hole candidate. It was observed in 2010 in NGC 6946, a grand-design spiral galaxy about 25 million light-years away. But it's about 10 times more distant than M31-2014-DS1. The candidate is named N6946-BH1, and it's progenitor was also a supergiant star. It blossomed in luminosity then slowly faded, just like the object in Andromeda.

The Hubble image on the left shows N6946-BH1 in 2007, but in its image of the same location in 2015, it's not there. Image Credit: NASA/ESA/C. Kochanek (OSU)

The Hubble image on the left shows N6946-BH1 in 2007, but in its image of the same location in 2015, it's not there. Image Credit: NASA/ESA/C. Kochanek (OSU)

Unfortunately, since N6946-BH1 is so far away, it was much fainter and the observational data isn't as high quality as it is for M31-2014-DS1. But with this new discovery, N6946-BH1 is relevant again.

“We've known that black holes must come from stars. With these two new events, we're getting to watch it happen, and are learning a huge amount about how that process works along the way,” said Morgan MacLeod, a lecturer on astronomy at Harvard and a co-author on the paper.

It took a lot of effort to find M31-2014-DS1. This work is the largest study ever done of variable infrared sources. They observed the stellar populations of the Milky Way and other nearby galaxies looking for objects like this, and found only one. While supernovae are hard to miss and announce their presence with months of extreme luminosity, direct-collapse black holes are the opposite.

“Unlike finding supernovae which is easy because the supernova outshines its entire galaxy for a few weeks, finding individual stars that disappear without producing an explosion is remarkably difficult,” De said.

Astronomers almost missed this one, buried in mounds of astronomical data. The question is, how many more are out there? How common are they?

“It comes as a shock to know that a massive star basically disappeared (and died) without an explosion and nobody noticed it for more than five years,” De said. “It really impacts our understanding of the inventory of massive stellar deaths in the universe. It says that these things may be quietly happening out there and easily going unnoticed.”

Like many issues in astronomy and astrophysics, only a larger sample and better observations can advance our understanding of these direct-collapse black holes. The Vera Rubin Observatory has the potential find many more of them in its decade long Legacy Survey of Space and Time.