We all know people that seem to defy aging and appear much younger than they actually are. This same phenomenon happens in astronomy, too. Some stars just don't seem to age the same way other stars do.

Blue Stragglers are puzzling in this regard. Blue Straggler Stars (BSS) were discovered decades ago and astronomers have been puzzling over them ever since. They get their name from their position on the Hertzsprung-Russell (HR) diagram. They're found in open clusters and globular clusters, and when compared to their same-aged cluster-mates, they're hotter and bluer.

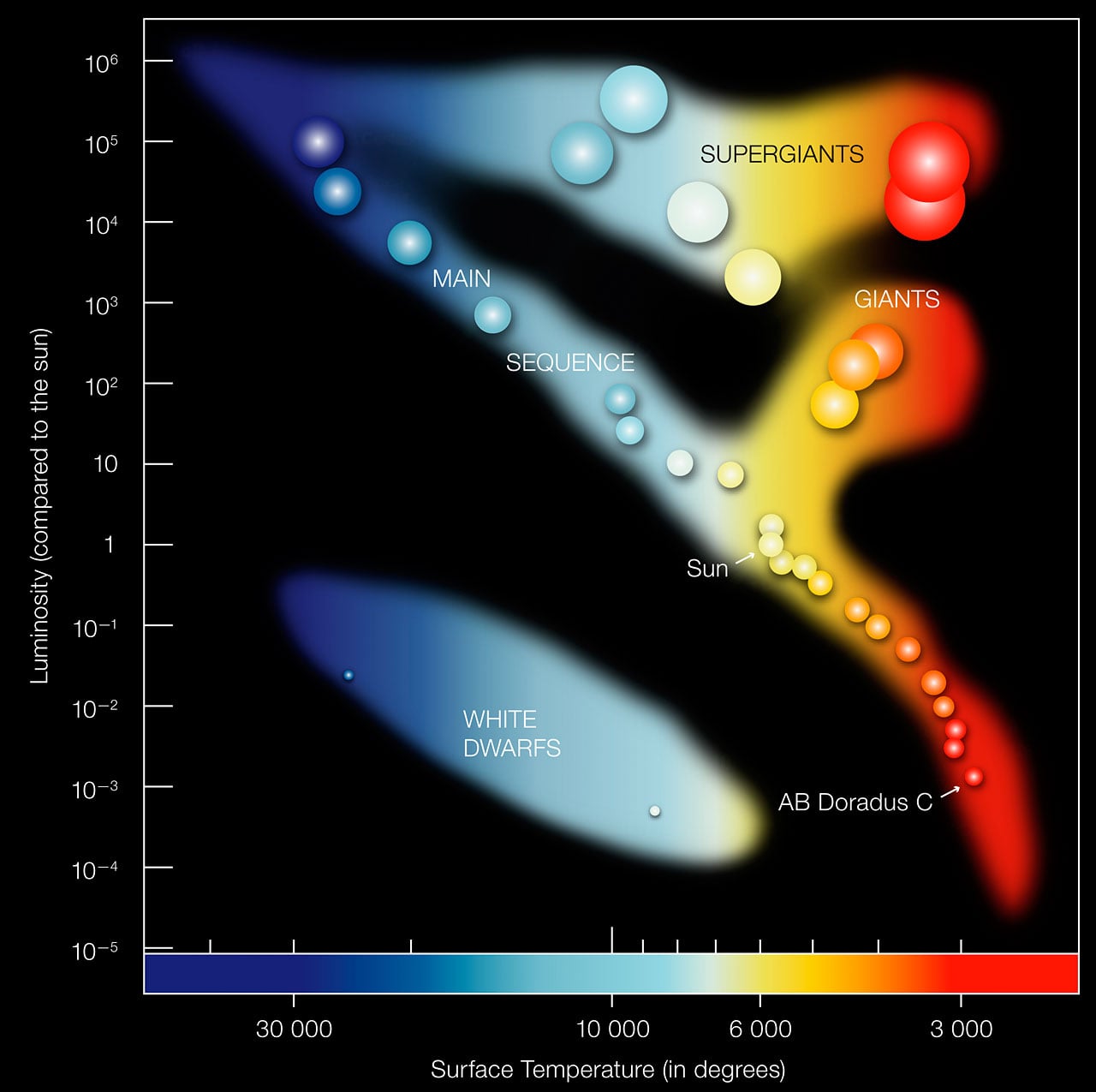

In the HR diagram, stars find their place based on their temperatures and luminosities. Main sequence stars spend their lives on a diagonal band in the HR diagram. Stars spend most of their lives here as they fuse hydrogen into helium. Our Sun fits in the middle of this band.

But more massive stars are hotter and brighter, and they're found in the upper left, while smaller stars, which are dimmer and cooler, are found on the bottom right.

*The Hertzsprung-Russell diagram organizes stars by their temperature and luminosity. Main sequence stars are in a diagonal band from the upper left to the lower right. More massive stars, which are hotter and brighter, are on the upper left. Smaller, dimmer, cooler stars are on the bottom right. Image Credit: ESO*

*The Hertzsprung-Russell diagram organizes stars by their temperature and luminosity. Main sequence stars are in a diagonal band from the upper left to the lower right. More massive stars, which are hotter and brighter, are on the upper left. Smaller, dimmer, cooler stars are on the bottom right. Image Credit: ESO*

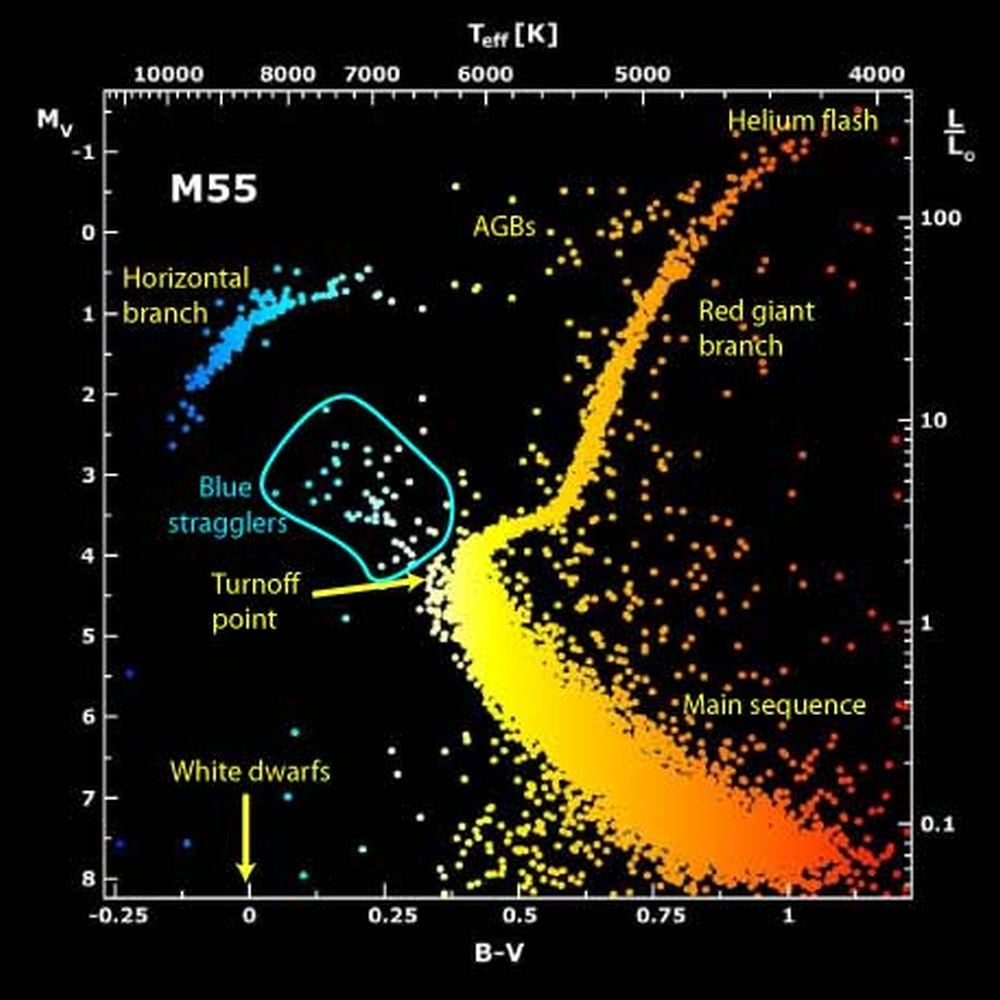

Blue Stragglers are found in globular clusters and are off on their own in the HR diagram.

This is an HR diagram for the globular cluster M55. It illustrates how blue stragglers are off on their own, straggling behind their fellow cluster members. Image Credit: NASA APOD Feb 23rd 2001.

This is an HR diagram for the globular cluster M55. It illustrates how blue stragglers are off on their own, straggling behind their fellow cluster members. Image Credit: NASA APOD Feb 23rd 2001.

Globular clusters are ancient structures that contain mostly older, redder stars. Blue stragglers stand out because they're hotter and brighter than their fellows. A cluster has a main sequence turn-off point, where stars cease hydrogen fusion and leave the main sequence to become giants. But blue stragglers don't conform to this. While the other stars become red, swollen, and cooler, blue stragglers stay blue, hot, and bright, even though they're the same age.

The only way they can do this is to acquire extra mass at some point. For decades, astrophysicists have debated how that might happen. There are two competing explanations for how BSS acquire their extra mass.

The first is via stellar collisions. Two stars and collide and then merge, creating a more massive, hotter, and bluer star. Stars are packed very tightly together in the cores of globular clusters, and stellar mergers would be more likely in this type of crowded environment.

The second way that BSS could acquire extra mass that can prolong their stay on the main sequence is via mass transfer. In a binary star arrangement, when one of the stars evolves into a giant, it becomes weaker gravitationally and can't hold onto its mass. In that case, the primary star draws mass from its companion, accretes it, and thereby become a blue straggler.

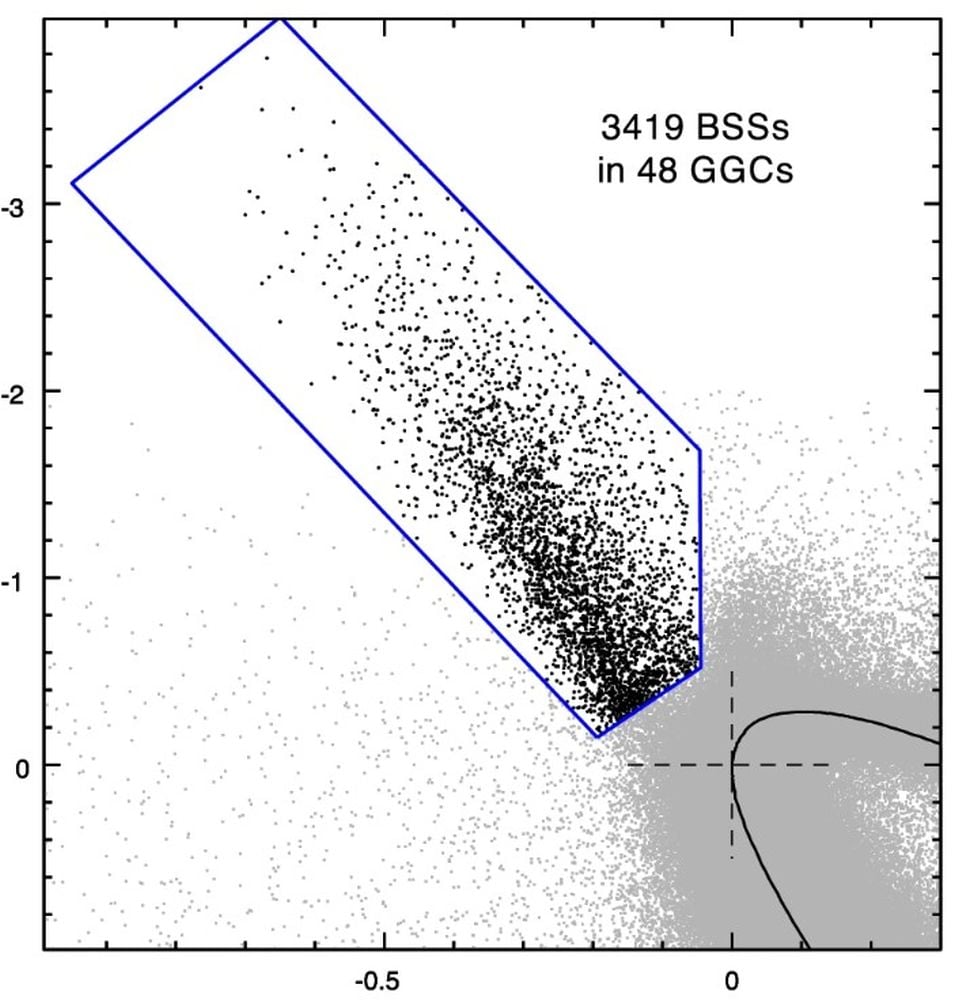

In new research, a team of astronomers examined BSS in 48 different galactic globular clusters (GCC) with the Hubble Space Telescope. They've built the largest catalogue of blue stragglers ever created, and wanted to determine if dense environments in GCCs were responsible for blue stragglers from stellar mergers. Some of the clusters in their work held as few as 12 blue stragglers, and some had as many as 179, with the total number of stragglers reaching 3,419.

Their research is titled "A binary-related origin mediated by environmental conditions for blue straggler stars," and it's published in Nature Communications. The lead author is Francesco Ferraro, a professor in the Department of Physics and Astronomy at the University of Bologna in Italy.

This figure from the study shows the 3,419 blue stragglers in the study, found among 48 galactic globular clusters. Image Credit: Ferraro et al. 2026. NatComm.

This figure from the study shows the 3,419 blue stragglers in the study, found among 48 galactic globular clusters. Image Credit: Ferraro et al. 2026. NatComm.

"Blue stragglers are anomalously massive core hydrogen-burning stars that, according to the theory of single star evolution, should not exist," Ferraro and his co-authors write. "They are suspected to form in mass-enhancement processes, involving binary evolution or stellar collisions."

"In dynamically active systems like globular clusters, the number of blue stragglers originated by collisions is expected to increase with the local density and the rate of stellar encounters," the researchers explain.

But that's not what their observations uncovered. Rather than finding more BSS in the dense center of globular clusters, they found more in lower-density regions.

"However, the most intriguing result comes from the comparison between the BSS specific frequency and other properties characterizing the cluster environment, such as the central density and the collision rate," the researchers explain in their study. "In fact, while high-density high-collisional environments are expected to favor the activation of the BSS collisional channels, we find instead that the BSS specific frequency decreases in these conditions."

"More specifically, in high-density conditions, the efficiency of BSS formation/survival is up to 20 times lower than in “peaceful”, low-density environments," they add.

These results chip away at the idea that stellar mergers are the cause of BSS. But they bolster the idea that they get their extra mass from binary partners. Binary partners are more likely to survive longer in the less dense regions of globular clusters.

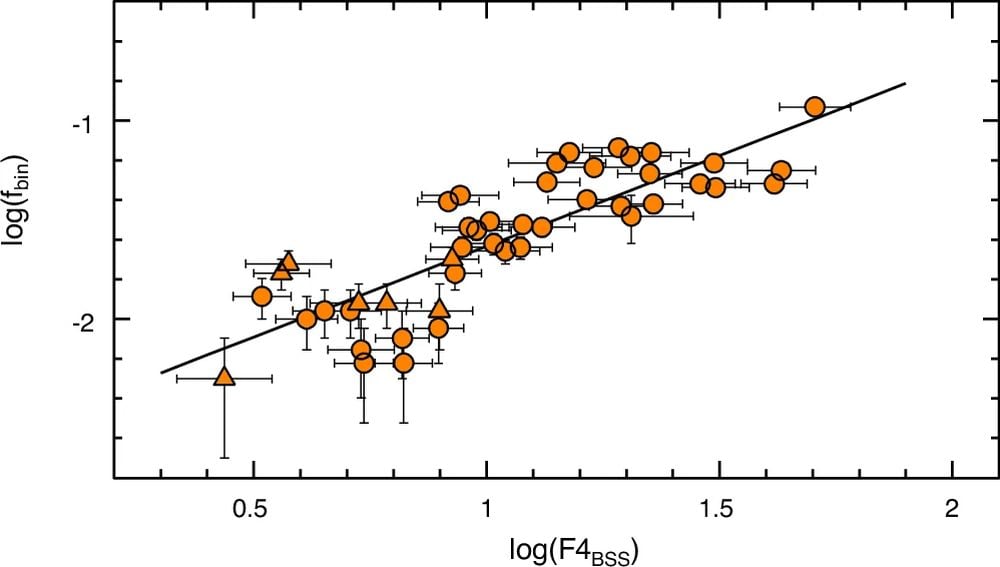

"These findings not only show that binaries preferably form/survive in low-density environments, but also suggest that the overall amount of binary systems hosted in the parent cluster could be the key parameter responsible for the observed BSS populations," the researchers explain.

This figure from the research shows the correlation between the fraction of binaries hosted in a galactic globular cluster (y-axis) and the blue straggler specific frequency (x-axis). A solid black line represents the best-fit relation to the data. Image Credit: Ferraro et al. 2026. NatComm.

This figure from the research shows the correlation between the fraction of binaries hosted in a galactic globular cluster (y-axis) and the blue straggler specific frequency (x-axis). A solid black line represents the best-fit relation to the data. Image Credit: Ferraro et al. 2026. NatComm.

Scientsts are cautious by nature, and they know that correlation does not equal causation. The authors are quick to point out something important. "The observed correlations, on their own, cannot be considered as irrefutable proofs of the physical connection between BSSs and binaries," they write.

But scientists also aren't in the habit of dismissing patterns that emerge from data. "However, the fact that the correlations observed for binary systems properly reproduce those found for BSSs, while they fail if other sub-populations are considered, supports the BSS-binary link," Ferraro and his fellow authors explain.

“This work shows that the environment plays a relevant role in the life of stars,” said lead author Ferraro in a press release. “Blue straggler stars are intimately connected to the evolution of binary systems, but their survival depends on the conditions in which they live. Low-density environments provide the best habitat for binaries and their by-products, allowing some stars to appear younger than expected.”

Co-author Enrico Vesperini from Indiana University echoes what Ferraro said. "Crowded star clusters are not a friendly place for stellar partnerships,” he explains. “Where space is tight, binaries can be more easily destroyed, and the stars lose their chance to stay young."

Stars are shaped by their surroundings, an uncontroversial statement. But the details of how they're shaped is not easily proven. This work draws a link between the stellar environment and one of the most puzzling types of stars out there. The results might seem counterintuitive, but they're backed up by a large sample.

“This work gives us a new way to understand how stars evolve over billions of years,” said co-author Barbara Lanzoni, also from the University of Bologna in Italy. “It shows that even star lives are shaped by their environment, much like living systems on Earth.”