A team of astronomers has recently completed a long-range observation of a comet far from the Sun. This analysis proves that there’s lots going on, even in the icy depths of the solar system.

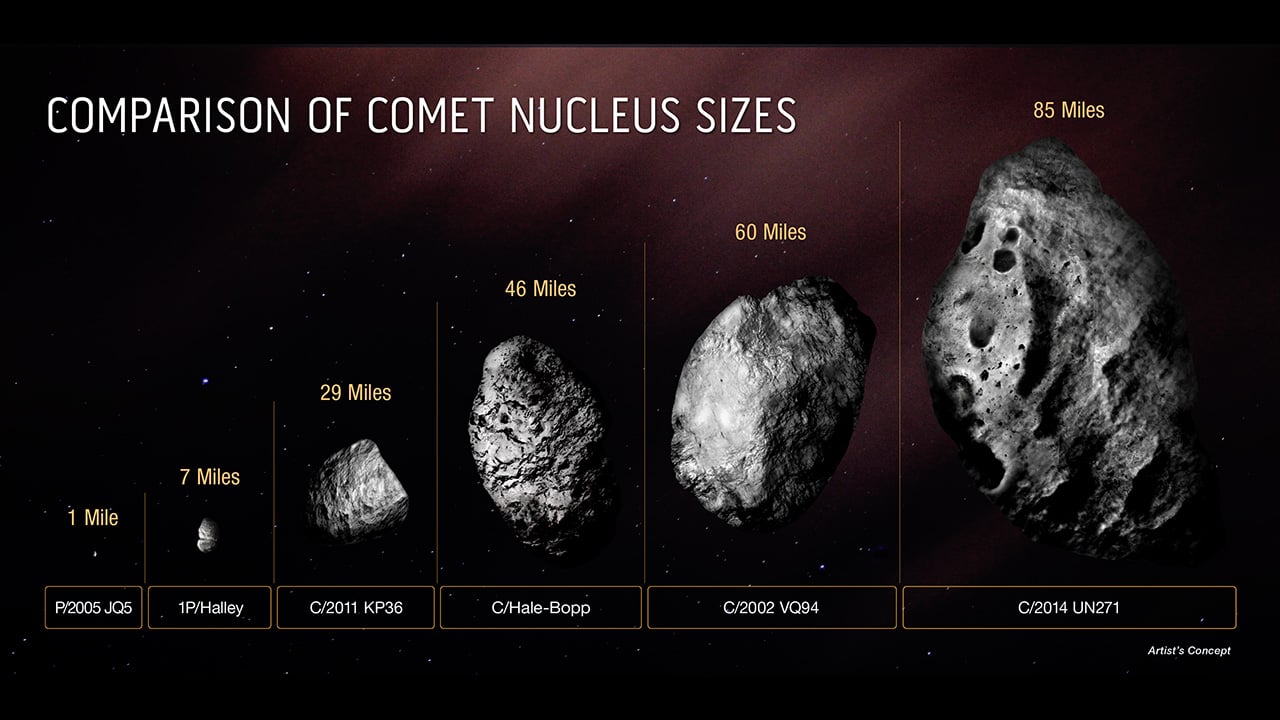

The targeted comet is C/2014 UN271 Bernardinelli-Bernstein. Comet UN271 is one of the largest Oort Cloud comets ever observed, measuring 140 kilometers across. It's currently at a distance of 16.5 Astronomical Units (AU) from the Sun, which makes it tough to observe with all but the largest telescopes. Astronomers have used the powerful Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile to observe the comet, watching as jets of carbon monoxide gas are erupting from its nucleus. This is a surprising level of activity for a comet that's so far from the Sun.

ALMA telescopes on the Chajnantor Plateau. Credit: ALMA/NSF/ESO

ALMA telescopes on the Chajnantor Plateau. Credit: ALMA/NSF/ESO

Comet UN271 was discovered in 2014 by astronomers Gary Bernstein and Pedro Bernardinelli. They noticed the faint fuzzball in archival images from the Dark Energy Survey, moving slowly as a +22nd magnitude smudge through the constellation Sculptor.

Almost immediately, astronomers knew Comet UN271 was something special, as its slow motion through the sky suggested it was far out in the solar system, and therefore quite large. After following the comet for a bit, astronomers realized it was 29 AU from the Sun at the time of discovery—about ¾ of the way to Pluto from the Sun—and had a nucleus about 120 kilometers (75 miles) across. For context, Halley’s Comet has a nucleus just 15 kilometers across. This puts Comet UN271 up there in terms of size, as the largest Oort Cloud comet seen to date.

The discovery image for Comet UN271 (annotated). Credit: NOIRLab.

The discovery image for Comet UN271 (annotated). Credit: NOIRLab.

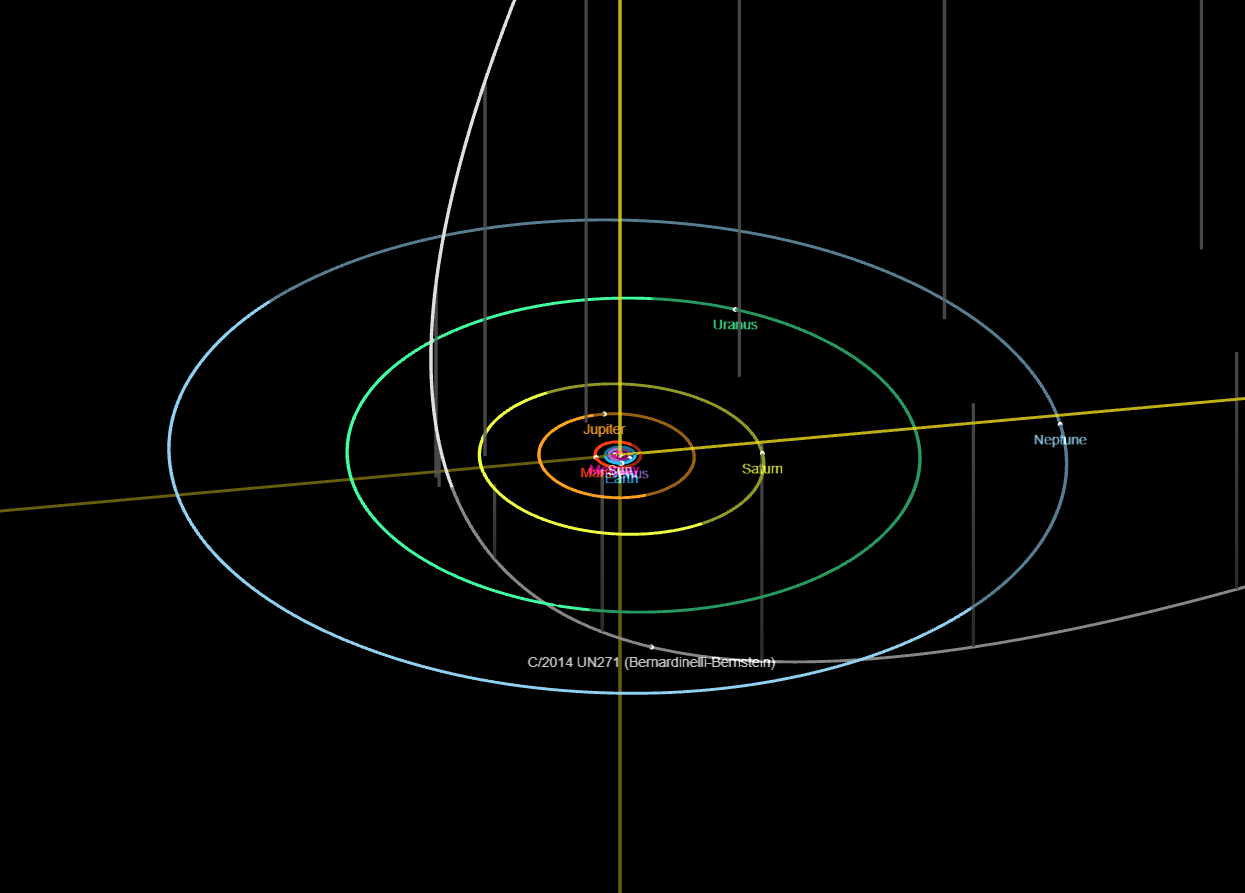

We’re fortunate to see Comet UN271 on its perihelion approach. In January 2031, the comet will pass 10.9 AU from the Sun, just outside the orbit of Saturn. On a 2.8-million-year orbit inbound, the comet will then head out of the solar system on a 4.6-million-year orbit outbound, for a far-off aphelion 55,000 AU from the Sun. That’s 87% of a light-year away, about a fifth of the way to Proxima Centauri, the nearest star.

The orbit of Comet UN271 through the solar system. Credit: NASA/JPL Horizons.

The orbit of Comet UN271 through the solar system. Credit: NASA/JPL Horizons.

The difference in orbit inbound versus outbound for the comet is due to its interaction with solar system planets while it's near the Sun. Any new comet entering the inner solar system stands about a 40% chance of having its orbit altered. Likely, Comet UN271 was knocked off its Oort Cloud perch by a stellar pass near the solar system that sent sunward, long ago.

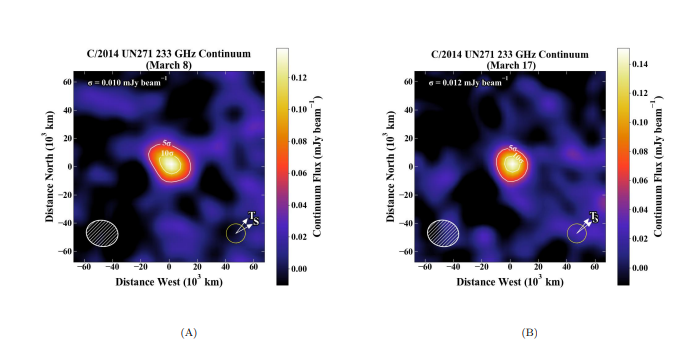

Looking at a cold distant object like Comet UN271 really pushed the sensitivity and resolution of ALMA to its limits. The thermal signal received by ALMA will not only help to refine the comet’s size, but also help to chronicle the dust production rate seen.

"These measurements give us a look at how this enormous, icy world works," says Nathan Roth (NASA/GSFC) in a recent press release. "We're seeing explosive outgassing patterns that raise new questions about how this comet will evolve as it continues its journey towards the inner solar system."

False color images of Comet UN271, showing activity. Credit: ALMA/NSF/ESO.

False color images of Comet UN271, showing activity. Credit: ALMA/NSF/ESO.

Not only was this a record-setting detection in terms of distance, but it also demonstrates that comets can still display activity, far from the Sun.

No missions are planned to give us a view of Comet UN271 up close. The European Space Agency does have a mission named Comet Interceptor in the works that would loiter in the inner solar system, ready to chase down the next big comet. Comet Interceptor is planned for launch in 2029.

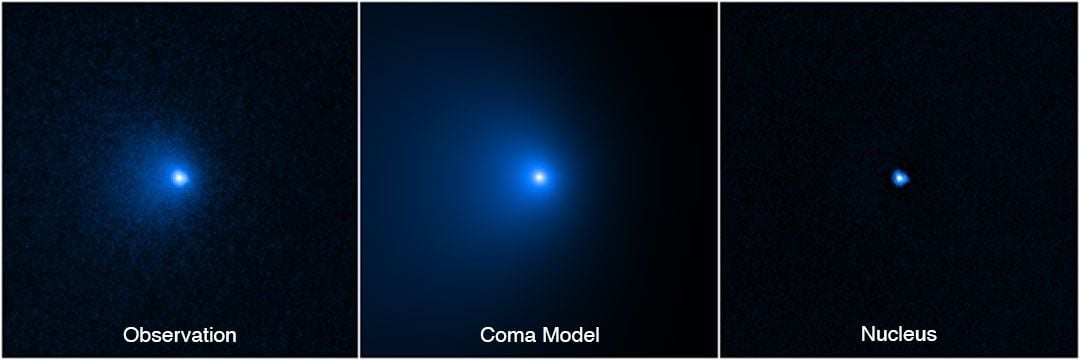

The Hubble Space Telescope imaged Comet UN271 in January 2022. We should get good views of the comet from the James Webb Space Telescope leading up to perihelion if it's ever tasked to observe it. The Vera Rubin Observatory, which is set to reveal its very first images next week could provide amazing views of the comet as well in the years to come.

Hubble's view of Comet UN271 in 2022. Credit: NASA/HST/STScI

Hubble's view of Comet UN271 in 2022. Credit: NASA/HST/STScI

And yes, a comet the size of UN271 would spell a bad day for Earth, though in this case, it isn’t coming anywhere near the inner solar system. UN271 is 12 times the size of the Chicxulub impactor (which was only about 10 kilometers across) that struck the Earth 66 million years ago, so it would definitely be an extinction-level event if something the size of UN271 ever came our way.

A size comparison for other known comets, versus UN271. Credit: NASA/ESA/Zena Levy/STScI

A size comparison for other known comets, versus UN271. Credit: NASA/ESA/Zena Levy/STScI

Too bad Comet UN271 won’t visit the inner solar system... (just not too close!) It’s bigger than Hale-Bopp, and would provide an amazing show. For now, we’ll have to wait for the next Oort Cloud interloper to turn up. Still, the appearance of Comet UN271 shows us just what might be lurking out there, in the remote realms of the outer solar system.