Radio astronomy has a pollution problem. Satellites thousands of kilometres overhead, designed to broadcast communications or relay data, are increasingly contaminating the frequencies astronomers use to study the universe. While much attention has focused on SpaceX's Starlink and other low Earth orbit constellations, but what about the satellites much farther away?

At 36,000 kilometres altitude, hundreds of satellites orbit in a special zone called geostationary orbit, moving at exactly the same rate as Earth rotating beneath them. From the ground, they appear frozen in one spot of sky. These satellites handle everything from television broadcasts to military communications, and unlike their low orbit cousins that zip across the sky in minutes, geostationary satellites can remain within a telescope's field of view for hours.

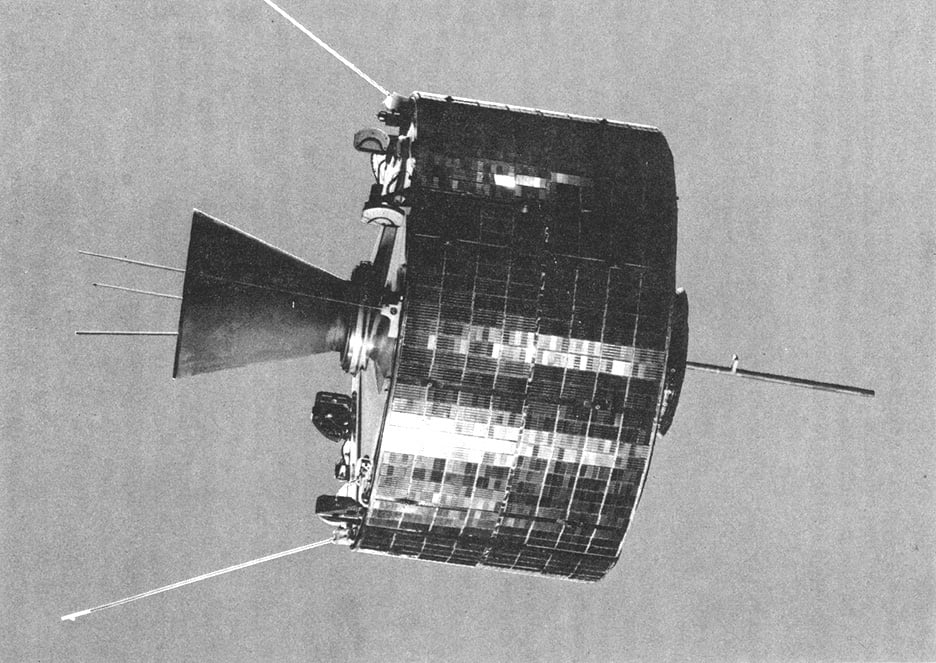

Syncom 2, the first geosynchronous satellite (Credit : NASA)

Syncom 2, the first geosynchronous satellite (Credit : NASA)

Until now, no one had systematically measured whether these distant satellites were leaking unintended radio emissions in the frequencies critical for astronomy. A team led by researchers at CSIRO's Astronomy and Space Science division has finally provided an answer, and it's mostly good news.

Using archival data from the GLEAM-X survey captured by Australia's Murchison Widefield Array in 2020, the researchers analysed observations covering 72 to 231 megahertz, the low frequency range where the upcoming Square Kilometre Array will operate. They tracked up to 162 geostationary and geosynchronous satellites over a single night, stacking images at each satellite's predicted position to search for radio emissions.

The results reveal that the vast majority of these distant satellites remain invisible to radio telescopes in this frequency range. For most satellites, the team established upper limits better than 1 milliwatt of equivalent isotropic radiated power in a 30.72 megahertz bandwidth. The best limits reached an impressively low 0.3 milliwatts.

Only one satellite, Intelsat 10-02, showed possible detection of unintended emission at around 0.8 milliwatts. Even this potential culprit remained well below typical emission levels seen from low Earth orbit satellites, which can radiate hundreds of times more powerfully.

Artist's impression of the 5km diameter central core of Square Kilometre Array (SKA) antennas (Credit : SPDO/TDP/DRAO/Swinburne Astronomy Productions)

Artist's impression of the 5km diameter central core of Square Kilometre Array (SKA) antennas (Credit : SPDO/TDP/DRAO/Swinburne Astronomy Productions)

The distinction matters because of distance and geometry. Geostationary satellites sit ten times farther from Earth than the International Space Station orbits. At that distance, even relatively strong radio emissions fade to faint whispers by the time they reach telescopes on the ground. Moreover, the study's observation strategy, pointing near the celestial equator, meant each satellite remained in the telescope's wide field of view for extended periods, allowing sensitive stacking techniques that would reveal even intermittent emissions.

The Square Kilometre Array in Australia and South Africa, will once completed, be orders of magnitude more sensitive than current instruments in the low frequency range. What appears as harmless background noise to today's telescopes could become devastating interference for SKA. These new measurements provide crucial baseline data for predicting and mitigating future radio frequency interference.

As satellite constellations proliferate and radio telescopes grow more sensitive, the pristine radio quiet that astronomers have long relied upon is slowly vanishing. Even satellites designed to avoid certain protected frequencies can leak unintended emissions through electrical systems, solar panels, and onboard computers. For now, geostationary satellites appear to be respectful neighbours in the low frequency radio spectrum. Whether they remain so as technology evolves and traffic increases remains an open question.