A recent study addresses possible effects from increased rocket launches on the ozone layer.

Spaceflight is literally taking off in a big way in 2025, and with it, we’ll need to start considering the impact it will have on the environment, including the atmosphere and the ozone layer.

A recent study looked at the challenges New Space may face, in terms of impact on the ozone layer. The study was published recently in the journal of Nature by researchers out of University of Canterbury in Christchurch, New Zealand, Harvard University, and the Institute for Atmospheric Climate Science and the Physics-Meteorology Observatory in Switzerland.

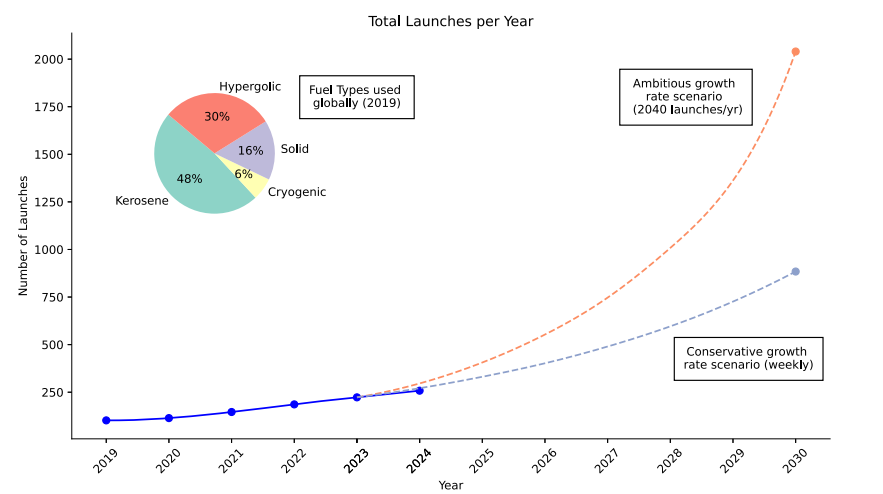

The study looked at two scenarios: one ‘ambitious’ scenario would see launch cadence increase to over 2,000 per year... nearly 10 times the current rate. A more conservative scenario would see almost 900 launches per year...a level that we could be on track to exceed by just 2030 at present levels of increase.

The current and projected number of orbital launches through 2030. Credit: Climate and Atmospheric Science.

The current and projected number of orbital launches through 2030. Credit: Climate and Atmospheric Science.

The study used existing chemistry-climate models, which are ideally suited for the purpose.

"A rate of ~2,000 launches per year would lead to thinning the ozone layer by 0.3% as a 'near-global' average, with larger losses seen over the poles, especially Antarctica where we see ozone losses up to 3.9%," lead researcher Laura Revell (University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand) told Universe Today. "However, this estimate doesn't include massive new vehicles currently in development or the effects of reentry material, so can be considered a 'lower limit' estimate of the damage that could occur."

The chief pollutants in rocket exhaust are chlorine byproducts from solid rocket motor (SRM) propellant, and black carbon. The four common propellant types considered in the study include solid, hypergolic, cryogenic, and kerosene. All can deplete the ozone layer.

Though ozone is crucial, the role it plays wasn’t even discovered until the last century. Composed of two bonded oxygen molecules, ozone is key to filtering out dangerous ultraviolet UV(B) solar radiation. Ozone also plays a vital role in maintaining vertical temperature gradients in the atmosphere and moderating atmospheric circulation. Life depends on the ozone layer; no other planet or moon in our solar system has such a protective layer.

NASA experiments aboard the International Space Station are also busy measuring the recovery of the ozone layer:

This finding comes just as the ozone layer recuperates from chlorofluorocarbon (CFC) use in the mid-20th century. The international production of CFCs was banned by the Montreal Protocol in 1989. There’s a seasonal shift seen in the ozone layer, though increased rocket launches year-round could delay or even reverse this recovery.

The World Meteorological Organization/United Nations Environment Programme WMO/UNEP noted in their 2022 Scientific Assessment of Ozone Depletion the impact of rocket launches on the ozone, although the exact impact has been poorly studied to date.

Ozone recovery, observed and projected over the Antarctic. Credit: NASA

Ozone recovery, observed and projected over the Antarctic. Credit: NASA

Where rockets launch from matters as well. Currently, all orbital launch sites are located in the northern hemisphere, with the exception Rocket Labs’ Māhia Launch Complex One in New Zealand.

Ironically, although more launches come from the north, the growing number of reentries also disproportionately impact the global south.

Potential solutions

The researchers in the study propose that propellants that generate chlorine byproducts should be reconsidered, or at least tightly regulated. Second, black carbon-producing propellants need to be minimized wherever possible. Avoiding ammonium perchlorate in rocket propellants is also a good move.

Record Years for Rockets

We’ve seen the record number of orbital launches worldwide broken every year, from 2021 onward. 2024 saw 263 launches worldwide—and we’re already on track to break that in 2025, with 126 launches thus far as we head towards mid-year in early July.

A big driver of this acceleration is SpaceX, which now accounts for more than half of the orbital launches worldwide alone—more than any nation. On top of this, most of these are to fill out the company’s massive mega-satellite constellation: Starlink. 7,797 Starlinks are now in orbit with 12,000 initially planned for... a number it could hit in the next few years, with a possible extension for the constellation out to over 34,000 satellites.

SpaceX has a back-fill approach to Starlink, meaning new satellites will need to be launched to replenish older ones, as they succumb to obsolescence and atmospheric reentry. This means that reaching 800-plus launches a year by 2030 is entirely possible, especially as other players get into the mega-satellite constellation game.

A trail of Starlink satellites over Tucson, Arizona. Credit: Rob Sparks.

A trail of Starlink satellites over Tucson, Arizona. Credit: Rob Sparks.

Already, the U.S. Department of Defense is fielding Starshield (its own version of Starlink) and China is placing its own version of Starlink 1,000 Sails in space... Amazon’s Kuiper project is also set to carry out its second launch this week. SpaceX also has plans to launch more a hundred Starlinks at a crack from Starship, once the platform reaches orbit.

Switching fuels with oversight can also help. Startup BluShift aerospace may reach orbit with its Red Dwarf rocket currently in development and promotes itself as using a an eco-friendly, proprietary bio-fuel. China’s space startups to include Epoch Space are also working to use methalox fuels.

A SpaceX launch punches a hole in the ionosphere over Puerto Rico. Credit: Frankie Lucena.

A SpaceX launch punches a hole in the ionosphere over Puerto Rico. Credit: Frankie Lucena.

Certainly, some sort of international criteria need to be in place in terms of rocket launches versus ozone depletion, akin to maybe an updated version of the Montreal Protocol that takes New Space and its players into account. The study notes that New Zealand is actually the only nation thus far to put a cap on launches, to no more than once every 72 hours.

Players in New Space offer us both a prospect of an exciting new universe of connectivity... and an unplanned experiment on the Earth’s environment with an uncertain outcome. We’ll see what this message of crisis and opportunity brings, as satellites begin to dominate the twilight sky.