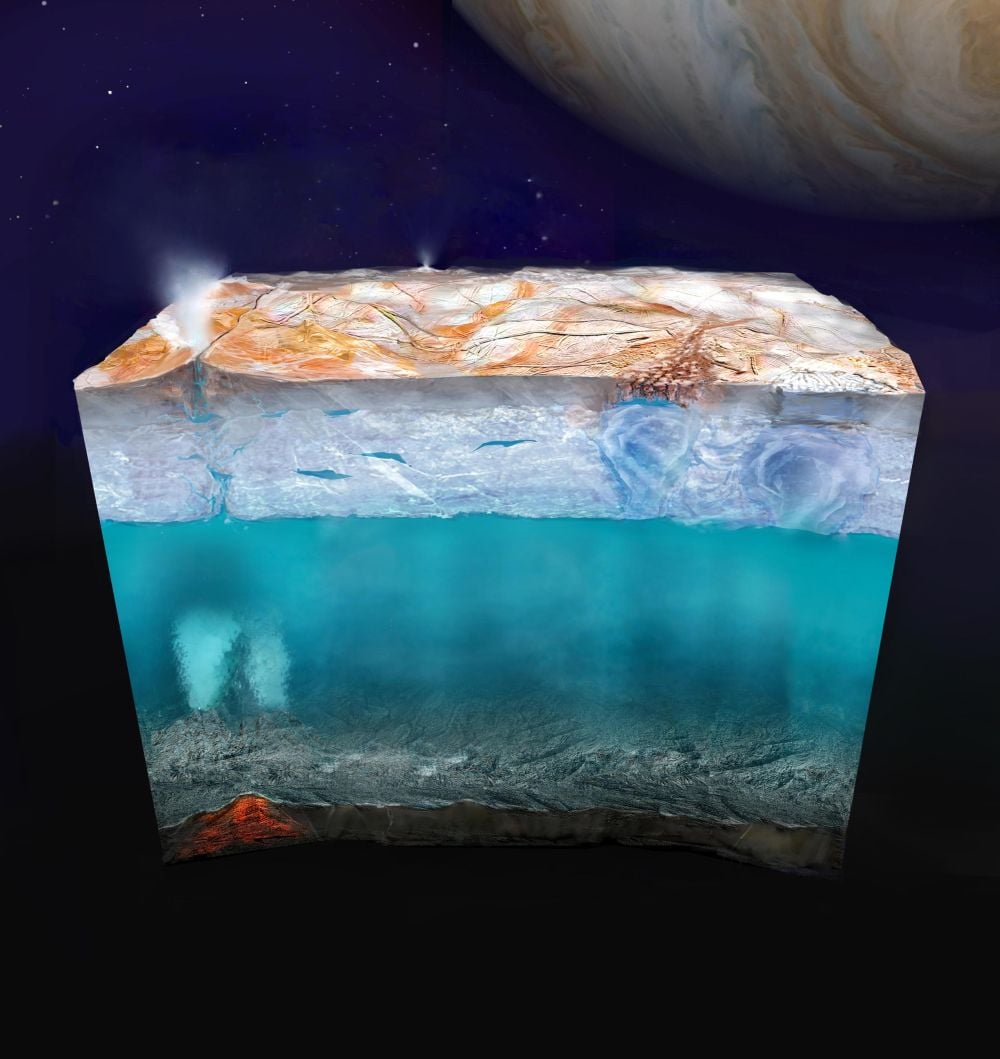

Jupiter's ice-covered moon Europa has emerged as a prime target in the search for life in our Solar System. Its frozen surface caps an ocean that contains more water than all of Earth's combined. Because it orbits the massive gas giant Jupiter, tidal heating keeps that ocean from freezing.

Scientists have observed water plumes escaping through cracks in Europa's icy cover, a strong indication of thermal activity in its oceans. The moon seems to have the necessary conditions for life: water, heat, and chemistry.

A critical part of its proposed habitability are thermal vents on its ocean floor. On Earth, hydrothermal vents exist when seawater penetrates into the Earth and is superheated by magma. The hot water turns acidic, and it leaches minerals from the rock. These minerals are then emitted from the vents. Scientists discovered life around these vents that use the minerals as an energy source, showing that life can exist in total darkness without sunlight.

Scientists have wondered if the same thing could be happening on Europa. In this case, the water is heated because of tidal heating on the moon. As it orbits Jupiter, Europa is stretched and squeezed, creating fractures in the ocean floor. Scientists think that water penetrates into the mantle, becoming heated. The heat creates the same type of mineral-rich venting as on Earth, according to research and simulations.

But new research in Nature Communications is placing a big question mark on this line of thinking. It's titled "Little to no active faulting likely at Europa’s seafloor today," and the lead author is Paul Byrne. Byrne is an associate professor of Earth, Environmental, and Planetary Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis.

"Many of the outer Solar System’s icy satellites feature known or suspected subsurface oceans, at least some of which are likely situated atop rocky interiors," the authors write. It's possible that water-rock interactions on these seafloors are similar to Earth, where faulting and hydrothermal systems create an environment where chemotrophs can thrive. "Absent such phenomena, however, any attainment of chemical equilibrium between the seafloor and ocean might limit the availability of chemical energy for life," the authors explain.

*This illustration shows what the interior of Europa may look like, with a thick ice cap and a deep ocean. The icy crust may hold pockets of water, and the seafloor may have hydrothermal vents. Image Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech*

*This illustration shows what the interior of Europa may look like, with a thick ice cap and a deep ocean. The icy crust may hold pockets of water, and the seafloor may have hydrothermal vents. Image Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech*

In their research, the scientists took into account all of the possible drivers of active faulting on Europa's seafloor: tidal flexing, global contraction, mantle convection, even serpentinization. Serpentinization is when rock absorbs an enormous amount of water, creating an exothermic reaction that can raise the rock temperature high enough to create hydrothermal vents.

"We find that none of these mechanisms is likely able to drive slip along even weak, pre-existing fractures in the present," the authors write.

“If we could explore that ocean with a remote-control submarine, we predict we wouldn’t see any new fractures, active volcanoes, or plumes of hot water on the seafloor,” lead author said Byrne said in a press release. “Geologically, there’s not a lot happening down there. Everything would be quiet.” And on an icy world like Europa, a quiet seafloor might well mean a lifeless ocean, he added.

“I’m really interested to know what that seafloor looks like,” Byrne said. “For all of the talk about the ocean itself, there has been little discussion about the seafloor.”

These results are based on modelling the strength and brittleness of the seafloor rock. They're also based on Europa's orbit, and its eccentricity, because eccentricity is what drives tidal flexing and heating. But the results show that the seafloor rock is much stronger than the tidal flexing from the moon's eccentric orbit. "The eccentricity required to drive faulting at a depth of 1000 m beneath the seafloor is 0.441, far higher than Europa’s present eccentricity of 0.009," the authors write in their research.

The authors acknowledge that it's possible that over long time-spans, the rock has been progressively weakened enough to allow for flexing-induced cracking. That would mean that seafloor faulting could take place. But that would only create shallow faulting, not the deep faulting required for vents. The tidal stressing would still be "twelve times too low to induce failure at a subseafloor depth of 1000 m.," the authors write.

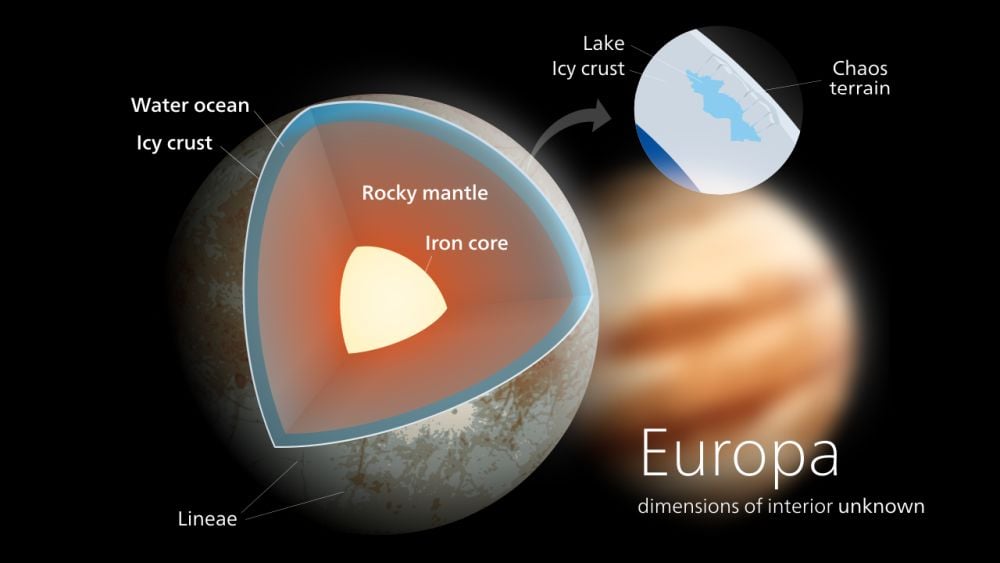

Europa is similar to Earth in some ways. It has a rocky core that likely maintained radiogenic heating for a time after formation, and may still have some today. But it's rocky mantle and core are much smaller than Earth's, and while Earth's radiogenic heating is still ongoing, Europa's may have died out long ago. In any case, it can't account for the heat that keeps the moon's ocean liquid. Tidal flexing must be providing it, but as this research shows, there's just not enough of it to create the active faulting and events on the seafloor necessary for habitability.

“Europa likely has some tidal heating, which is why it’s not completely frozen,” Byrne said. “And it may have had a lot more heating in the distant past. But we don’t see any volcanoes shooting out of the ice today like we see on Io, and our calculations suggest that the tides aren’t strong enough to drive any sort of significant geologic activity at the seafloor.”

When scientists first spotted plumes of water coming from Europa's south polar region with the Hubble Space Telescope, they assumed that the water was coming from the deep ocean. That interpretation favours the notion of habitability. But more recent research suggests that the plumes come from pockets of water trapped in the ice. Tidal flexing heats these pockets until they erupt in plumes. These plumes require no thermal vents and no seafloor faulting.

If the moon has a quiescent sea-floor like this research suggests, then it's highly unlikely that it's in any way habitable or able to support life. “The energy just doesn’t seem to be there to support life, at least today,” Byrne said.

It's too bad the the idea of Europa's habitability is taking a hit, because NASA's Europa Clipper mission to the moon launched in October, and the ESA's Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (JUICE) launched in 2023. Both missions were motivated by the moon's potential habitability, though they will still gather important scientific data.

Europa's icy shell is between 15 to 25 km thick, scientists think, and the ocean is global and is about 100 km thick. However, these measurements all come from remote data gathered by missions that weren't focused on the moon. JUICE and Clipper will study Europa more intently and hopefully deliver some more solid answers. Not only about how thick and deep these features are, but hopefully about their composition, their natures, and how they may interact and change over time.

*Europa has an inner core and mantle like Earth, but instead of a rocky crust, it has an icy one. Remote measurements and simulations show that the crust is between 15 and 25 km thick, and that the ocean is about 100 km thick, but those are uncertain numbers. The Europa Clipper and Juice will take more rigorous measurements. Image Credit: By Kelvinsong - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=23622820*

*Europa has an inner core and mantle like Earth, but instead of a rocky crust, it has an icy one. Remote measurements and simulations show that the crust is between 15 and 25 km thick, and that the ocean is about 100 km thick, but those are uncertain numbers. The Europa Clipper and Juice will take more rigorous measurements. Image Credit: By Kelvinsong - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=23622820*

These missions will also capture much clearer and detailed images of Europa's surface, and those will provide much more accurate measurments of the thickness of the ice and the ocean's depth. The spacecraft won't orbit the moon. Instead it'll perform a series of high speed dives that bring it to within 25 km of the moon's surface. “Those measurements should answer a lot of questions and give us more certainty,” Byrne said.

This research can't say for certain that Europa isn't habitable. It just pours cold water on the current thinking behind its potential habitability. There may be other ways that it could support life.

"For now, we posit that fracture-moderated habitability at and within Europa’s seafloor today is unlikely," the authors write. "Future studies of Europa’s modern habitability should focus on the generation of energy for chemoautotrophic life by mechanisms that do not require ongoing seafloor tectonics in the current epoch," they conclude.

While Europa may have taken a hit in terms of its potential habitability, the Milky Way is vast and there are many other planets and moons out there. There may be ocean moons in other solar systems with the right conditions for life.

“I’m not upset if we don’t find life on this particular moon,” Byrne said. “I’m confident that there is life out there somewhere, even if it’s 100 light-years away. That’s why we explore—to see what’s out there.”