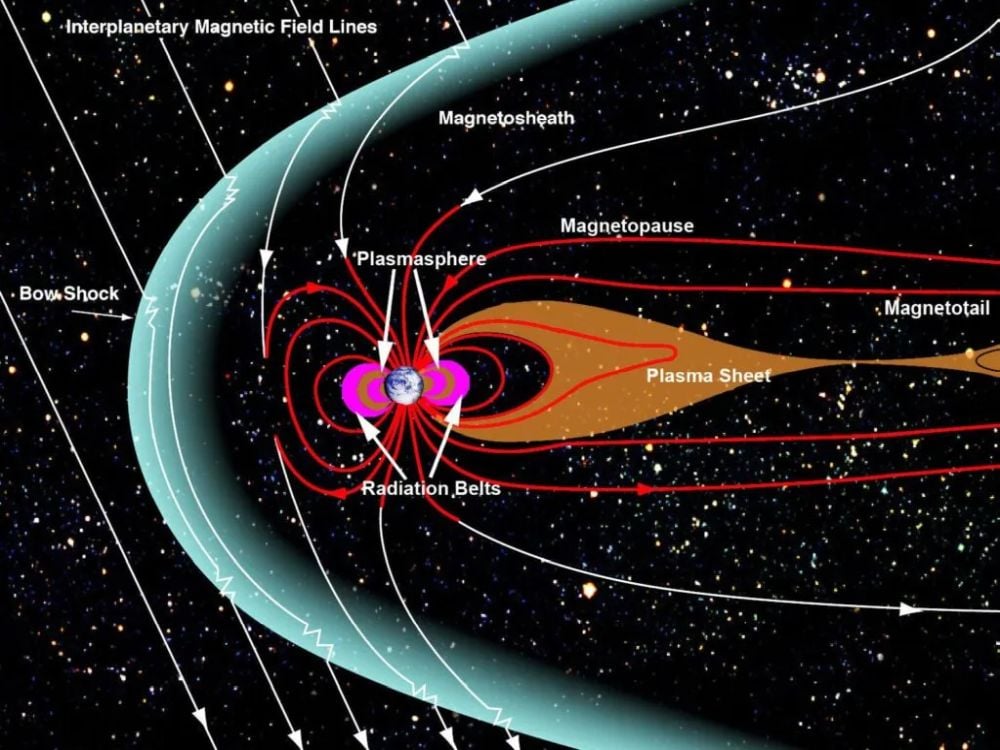

There are many reasons why Earth is habitable. One of them is that it's in a delicately balanced radiation struggle with the Sun and the larger cosmos. The Sun emits a powerful solar wind that would strip away the planet's atmosphere, except it's deflected by Earth's protective shield, the magnetosphere. Cosmic rays, dangerous high-energy particles that can damage living tissue, stream in from elsewhere in the cosmos, and they're likewise deflected by the magnetosphere.

Scientists are fairly certain that an exoplanet can only be habitable if it has protection from its star and from the cosmos. Earth's magnetic field is created by convection currents in the planet's outer liquid core, which contains iron and nickel. New research in Nature Astronomy shows that for one common type of exoplanet—super-Earths—a magma ocean could create the same type of protective shield. Super-Earths are the most common type of exoplanet, and if magma oceans can boost their habitability, the chances of life existing elsewhere are greater than thought, if this research is correct.

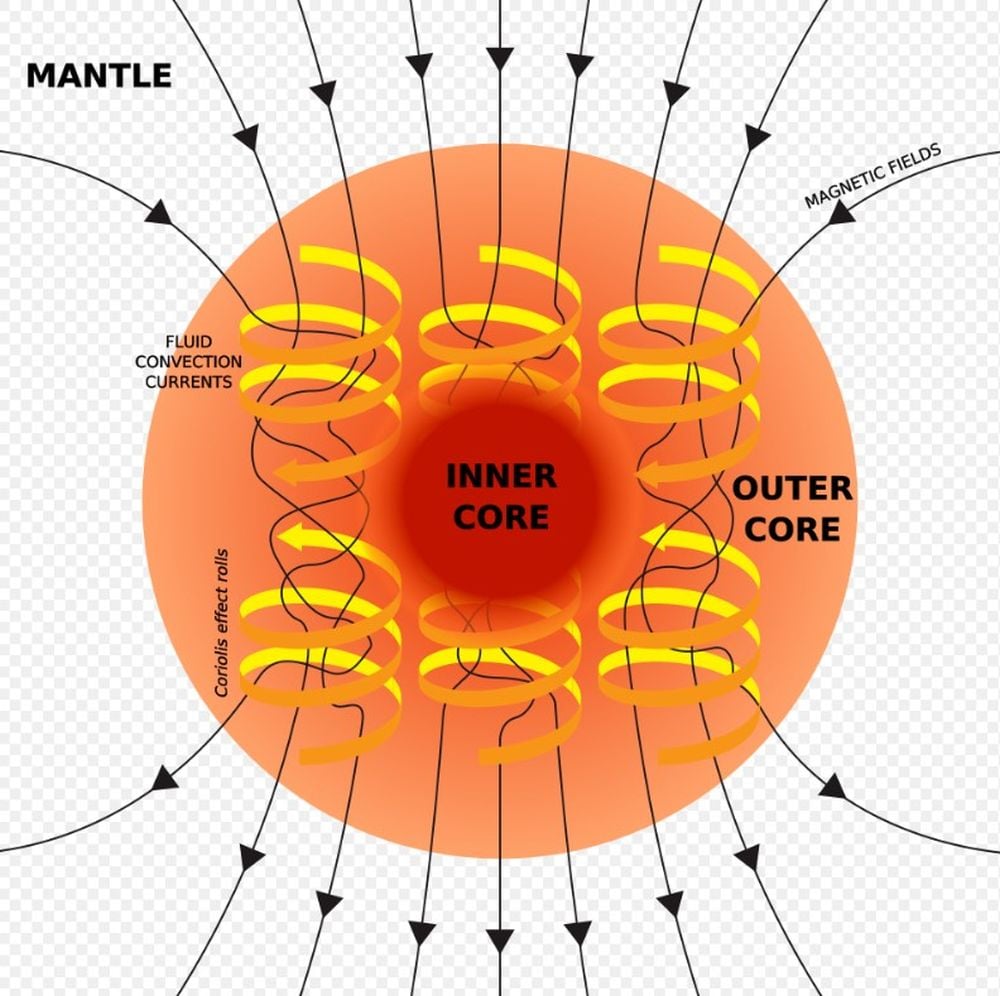

*This simple schematic shows how convective forces and the Coriolis force create a dynamo in Earth's outer core. Image Credit: By Andrew Z. Colvin - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=98901558*

*This simple schematic shows how convective forces and the Coriolis force create a dynamo in Earth's outer core. Image Credit: By Andrew Z. Colvin - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=98901558*

The research is titled "Electrical conductivities of (Mg,Fe)O at extreme pressures and implications for planetary magma oceans," and the lead author is Miki Nakajima, an associate professor in the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences at the University of Rochester.

"During planet formation, planets undergo many impacts that can generate magma oceans," the authors write. "When these crystallize, part of the magma densifies via iron enrichment and migrates to the core–mantle boundary, forming an iron-rich basal magma ocean (BMO)."

These BMOs could provide the same type of magnetic protection that Earth enjoys, but only if their iron content is high enough. "The BMO could generate a dynamo in early Earth and super-Earths if the electrical conductivity of the BMO, which is thought to be sensitive to its Fe content, is sufficiently high," the researchers explain.

While Earth's modern magnetosphere is generated by its outer core, that wasn't always the case. Paleomagnetic research shows that the planet's magnetic shield was active as long as 3.45 billion years ago, and maybe even earlier, by 4.2 billion years ago. Earth's shield comes from the outer core, but the inner core plays a role, too. When it crystallized, it released heat and light elements that were critical to the outer core's thermal and compositional convection. The problem is, research shows that this only happened about 700 million years ago.

The question is, what created Earth's early magnetic shield? The researchers point out that several existing models try to explain Earth's early geodynamo without a solid inner core, and each of them have their problems.

"An alternative, which is the main focus of this work, is dynamo generation in a basal magma ocean (BMO)," the authors write. A BMO is a deep layer of molten rock under a solid crust.

“A strong magnetic field is very important for life on a planet,” lead author Nakajima said in a press release, “but most of the terrestrial planets in the solar system, such as Venus and Mars, do not have them because their cores don’t have the right physical conditions to generate a magnetic field. However, super-earths can produce dynamos in their core and/or magma, which can increase their planetary habitability.”

To test their idea, the research team performed experiments on an Fe-rich BMO analogue. "To test this hypothesis, here we conduct laser-driven shock experiments on ferropericlase," the authors write. These types of experiments mimic the extreme pressures and temperatures present inside super-Earths. They also ran simulations that "calculate the long-term evolution of super-Earths."

The results show that the extremely intense pressures inside super-Earths, which can have as many as 10 Earth masses, forces the molten rock in their deep mantles to become electrically conductive. This conductivity can last a long time, and can be much stronger than Earth's, boosting the potential habitability of this common type of planet. It also helps explain Earth's ancient magnetosphere.

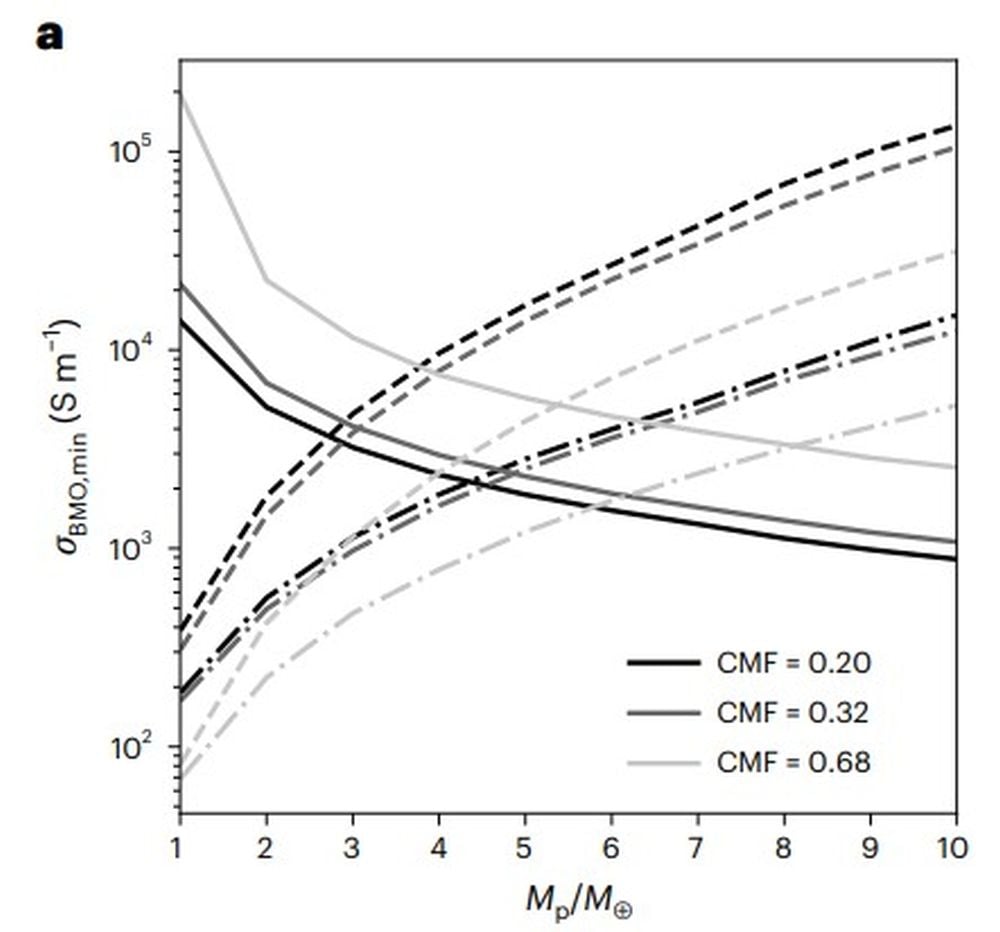

*This figure from the research illustrates the results. It shows the electrical conductivity for a BMO-driven dynamo and time evolution of the dynamo. The solid lines represent the minimum electrical conductivity required for dynamo generation in BMOs in super-Earths. The x axis is the planetary mass Mp normalized by the Earth mass M⊕. The black, grey and light grey lines correspond to Core Mass Fractions of 0.20, 0.32 and 0.68. A CMF of 0.20 is Mars-like, 0.32 is Earth-like, and 0.68 is Mercury-like. Image Credit: Nakajima et al. 2026 NatAstr*

*This figure from the research illustrates the results. It shows the electrical conductivity for a BMO-driven dynamo and time evolution of the dynamo. The solid lines represent the minimum electrical conductivity required for dynamo generation in BMOs in super-Earths. The x axis is the planetary mass Mp normalized by the Earth mass M⊕. The black, grey and light grey lines correspond to Core Mass Fractions of 0.20, 0.32 and 0.68. A CMF of 0.20 is Mars-like, 0.32 is Earth-like, and 0.68 is Mercury-like. Image Credit: Nakajima et al. 2026 NatAstr*

The experiments and model show that dynamos created by basal magma oceans are most likely stronger than those created by core-driven dynamos, at least for super-Earths with masses greater than about 3 to 5 Earth masses. "The BMO-driven dynamo can last for a few billion years, which may be detectable with future observations of super-Earths," the authors write. "These experiments and models contribute to an emerging picture of exoplanet habitability and provide support for the presence of a dynamo, even if the core itself cannot produce a dynamo."

The closer a planetary dynamo is to a planet's surface, the stronger the magnetic shield is. Taken together, the results not only explain super-Earth magnetic shields, but also the early Earth's magnetic shield that provided shelter while life on early Earth got started. "Thus, a BMO-driven dynamo can be the dominant source of the surface magnetic field for billions of years, which crucially includes the formative stages of planetary evolution," the authors write.

*Earth's magnetosphere protects our planet from dangerous radiation that can strip away the atmosphere and damage living tissue. The force of the solar wind pushes on it, creating the bow shock and the plasma sheet and magnetotail. Image Credit: NASA/Aaron Kaase*

*Earth's magnetosphere protects our planet from dangerous radiation that can strip away the atmosphere and damage living tissue. The force of the solar wind pushes on it, creating the bow shock and the plasma sheet and magnetotail. Image Credit: NASA/Aaron Kaase*

Exoplanet scientists know that protective magnetospheres are critical to habitability. Figuring out how to detect and measure them is a critical and very challenging issue in exoplanet science. In 2021, the Hubble may have observed the very first exoplanet magnetosphere around Kepler-3b, an exo-Neptune about 122 light-years away. However, the detection is still somewhat ambiguous, and illustrates the difficulty in detecting them. From such a great distance, these fields are extremely weak.

Powerful radio-telescopes are likely the solution to detecting these fields. If we ever put a radio-telescope on the Moon, like FarView or FARSIDE, it should be able to study distant magnetic fields. New ground-based radio observatories could also do it, as could a mission like the Lunar Surface Electromagnetics Experiment (LuSEE-Night).

Like many things in astronomy, only better future observations can shed more light on the issue.

“This work was exciting and challenging, given that my background is primarily computational and this was my first experimental work,” Nakajima said. “I’m very grateful for the support from my collaborators from various research fields to conduct this interdisciplinary work. I cannot wait for future magnetic field observations of exoplanets to test our hypothesis.”