For a long time, scientists assumed that Earth's water was delivered by asteroids and comets billions of years ago. This coincided with the Late Heavy Bombardment (ca. 4.1 to 3.8 billion years ago), a period when planets and bodies in the Solar System experienced a much higher rate of impacts. According to this theory, the planets of the inner Solar System were unable to retain volatile elements such as water due to their proximity to the Sun. However, recent findings from the analysis of lunar rocks and regolith returned by the Apollo missions have cast doubt on this assumption.

After examining a large suite of lunar samples using high-precision triple oxygen isotopes, researchers from the Universities Space Research Association (USRA) concluded that meteorites in the Late Heavy Bombardment could only have supplied a small fraction of Earth's water. The research team was led by Dr. Tony Gargano at USRA’s Lunar and Planetary Institute (LPI) and the University of New Mexico (UNM). As they explain in their study, the Moon's surface record sets a hard limit on the delivery of volatiles, even by the most generous estimates.

On Earth, the movement of tectonic plates constantly renews the surface, effectively erasing all traces of ancient impacts. But on the Moon, which is airless and hasn't experienced geological activity for billions of years, the geological record since the Late Heavy Bombardment has been carefully preserved. For decades, scientists have analyzed samples returned by the Apollo astronauts to decipher this history using specific elements. This includes siderophile ("metal-loving") elements that are abundant in meteorites but scarce in the Moon's silicate crust.

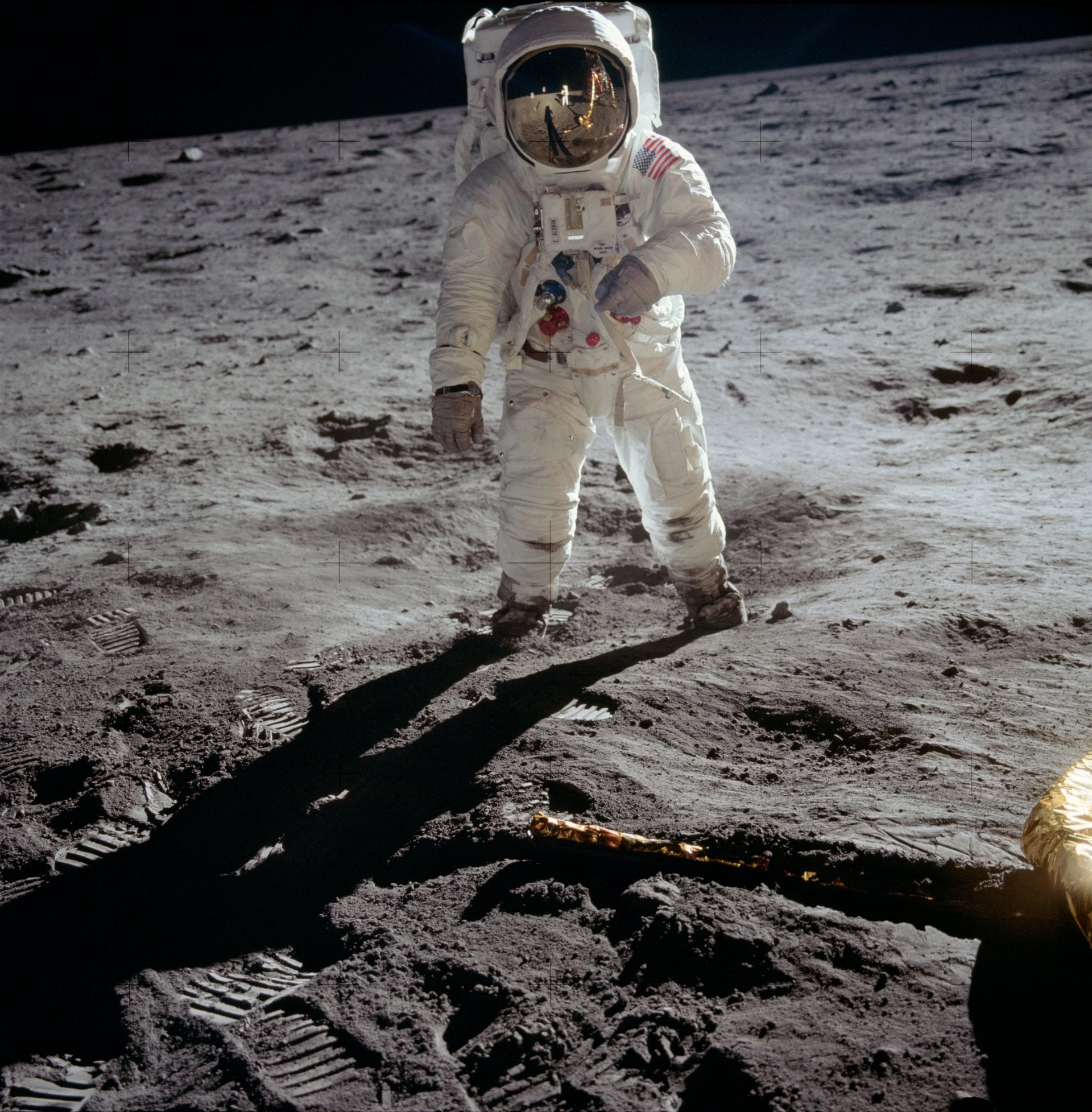

*Buzz Aldrin poses on the lunar surface during Apollo 11. Neil Armstrong, who took the photograph, is visible in Aldrin's visor. Credit: NASA*

*Buzz Aldrin poses on the lunar surface during Apollo 11. Neil Armstrong, who took the photograph, is visible in Aldrin's visor. Credit: NASA*

This is rather challenging because of the nature of regolith, which can melt and vaporize from impacts and repeatedly rework deposited materials. Similarly, geological processes can separate metal from silicate, complicating efforts to reconstruct the types of material and the quantities delivered. As Gargano explained:

The lunar regolith is one of the rare places we can still interpret a time-integrated record of what was hitting Earth’s neighborhood for billions of years. The oxygen-isotope fingerprint lets us pull an impactor signal out of a mixture that’s been melted, vaporized, and reworked countless times. Apollo samples are the reference point for comparing the Moon to the broader solar system.

When we put lunar soils and meteorites on the same oxygen-isotope scale, we’re testing ideas about what kinds of bodies were supplying water to the inner solar system. That’s ultimately a question about why Earth became habitable, and how the ingredients for life were assembled here in the first place.

Gargano and his colleagues took a different approach by focusing on oxygen isotopes rather than ("metal-loving" tracers), which make up the largest mass fraction of rocks. Its triple-isotope can also be used to separate two conflicting characteristics that are often confused in lunar regolith: the addition of impactor material and the effects that impact-induced vaporization has on isotopic composition. Upon measuring offsets in the oxygen-isotopes in the lunar samples, the team found that at least 1% of its mass consisted of impact-related material, likely from carbonaceous (C-type) meteorites that partially vaporized on impact.

From this, they set upper limits on the amount of water delivered to the Earth-Moon system by impactors, showing that only a tiny amount has been delivered since the Late Heavy Bombardment, compared to Earth's existing water. While oceans cover over 71% of the Earth's surface, water itself only accounts for about 0.023% of Earth's total mass. Nevertheless, this still works out to roughly 1.46 Sextillion (1.46 x 10²¹) kilograms, or 1.6 hundred quintillion tons! While meteorites might have delivered only a tiny fraction of that water, their contribution may have been very important for the Moon.

"Our results don’t say meteorites delivered no water,” said co-author Dr. Justin Simon from NASA’s ARES Division. “They say the Moon’s long-term record makes it very hard for late meteorite delivery to be the dominant source of Earth’s oceans.”

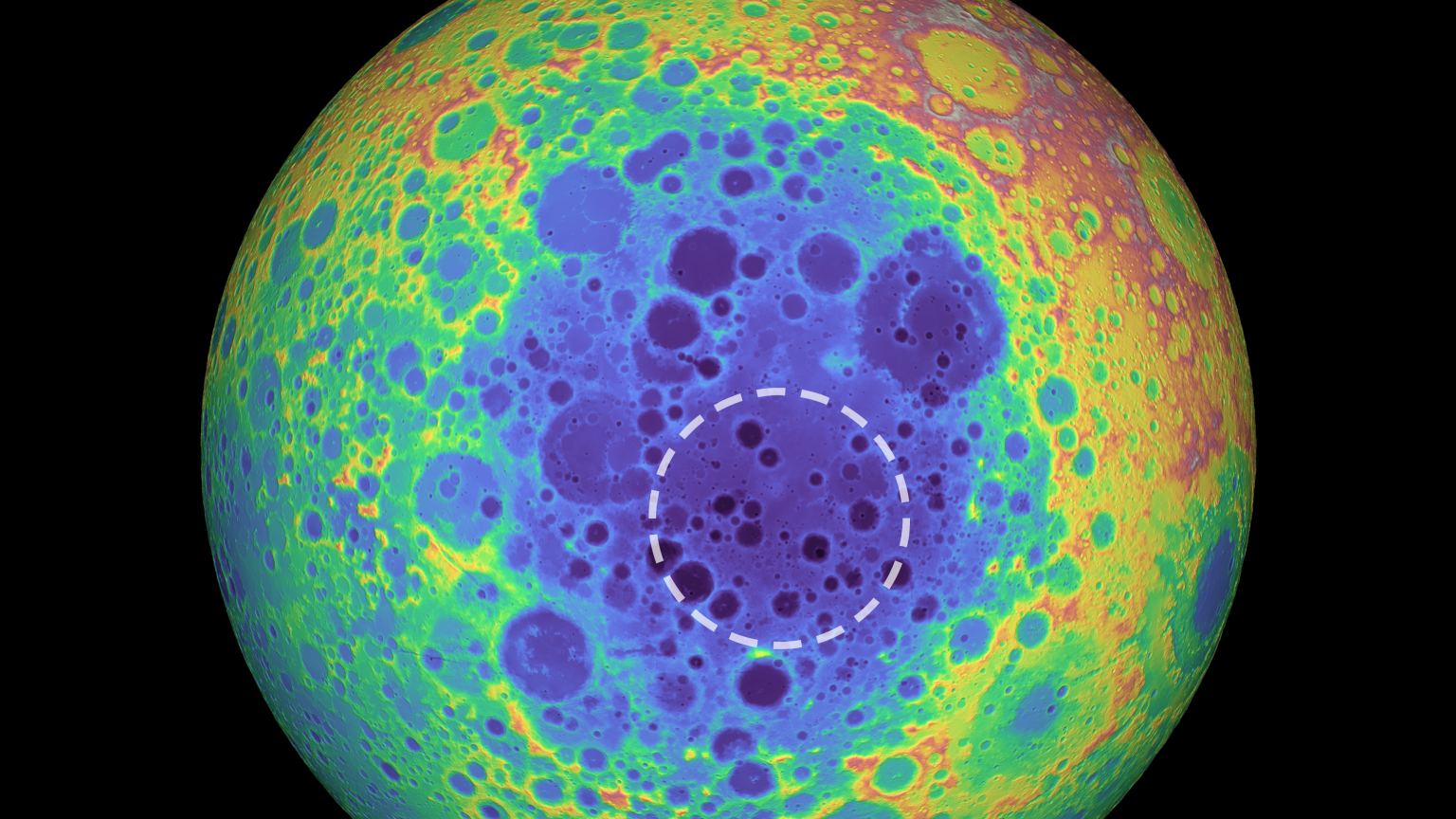

*The South Pole-Aitken basin on the lunar far side is one of the largest and oldest impact features in the solar system. Credit: NASA/GSFC/University of Arizona*

*The South Pole-Aitken basin on the lunar far side is one of the largest and oldest impact features in the solar system. Credit: NASA/GSFC/University of Arizona*

At present, the Moon's water inventory is largely concentrated in permanently shadowed regions (PSRs), which are typically found in the heavily cratered polar regions. For this reason, NASA and other space agencies - notably, the European Space Agency (ESA), the China Manned Space Agency (CMSA), and Roscosmos - have been planning to establish habitats in the South Pole-Aitken Basin. Ready access to water ice is essential for creating a sustained human presence, providing everything from drinking water and irrigation for crops to radiation shielding and the means to manufacture liquid hydrogen and oxygen propellant.

This presence will, in turn, allow for the creation of infrastructure vital to science, like radio telescopes that are unencumbered by interference from Earth and the Sun. Ergo, the small amount of water delivered by impacts could be the singlemost important factor enabling humanity's "Great Migration" to space. As Gerardo explained:

I’m part of the next generation of Apollo scientists—people who didn’t fly the missions, but who were trained on the samples and the questions Apollo made possible. The value of the Moon is that it gives us ground truth: real material we can measure in the lab and use to anchor what we infer from meteorites and telescopes.

The research team included scientists from UNM's Center for Stable Isotopes, the Institute of Meteoritics, the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), and the Astromaterials Research and Exploration Science Division (ARES) at NASA's Johnson Space Center. The paper detailing their findings was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science (PNAS)