For years the scientific consensus was that a supermassive black hole (SMBH) resides in the center of the Milky Way. There's plenty of evidence that the SMBH, named Sagittarius A-star, sits in the Galactic Center (GC). But there were still lingering doubts.

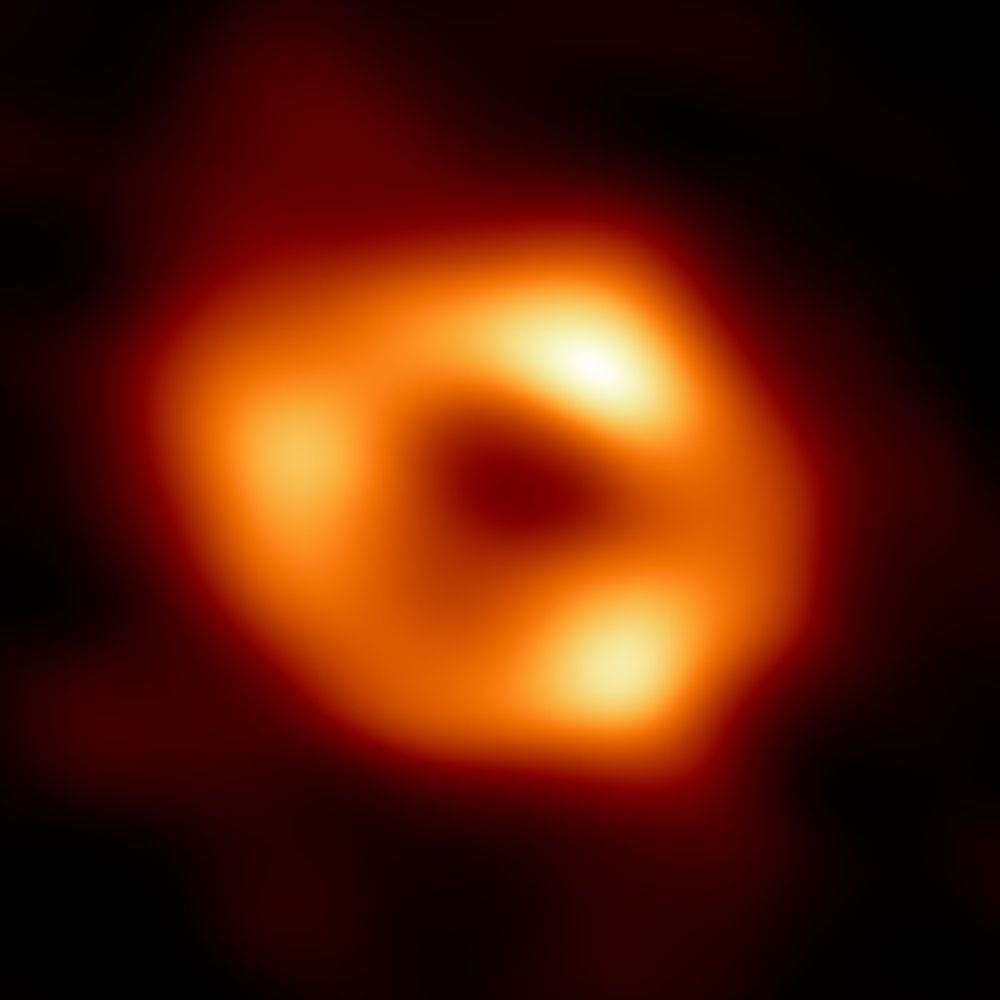

There's no doubt that something extraordinarily massive lurks in the GC, and that's exactly what an SMBH is. Some of the most powerful evidence in favour of a massive object is the S-stars. Their rapid orbits around the GC indicate the presence of an SMBH with about four million solar masses. There are also G-sources in the region, massive gas clouds whose orbits also signal the presence of a massive objects. Then in 2022, the Event Horizon Telescope seemed to seal the deal with its image of the SMBH's shadow surrounded by hot orbiting material.

But not everyone is totally convinced. Embedded deeply in the scientific literature are numerous research efforts suggesting that instead of a black hole, a massive object made of bosons or dark matter fermions sits in the Milky Way's GC. New research in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society supports the idea that's what really sitting in the Milky Way's GC is a massive clump of fermionic dark matter. The research is titled "The dynamics of S-stars and G-sources orbiting a supermassive compact object made of fermionic dark matter." The lead author is Valentina Crespi, from the Institute of Astrophysics La Plata in Argentina.

"Surrounding Sgr A-star, a cluster of young and massive stars coexist with a population of dust-enshrouded objects, whose astrometric data can be used to scrutinize the nature of Sgr A-star," the authors write. "An alternative to the black hole (BH) scenario has been recently proposed in terms of a supermassive compact object composed of self-gravitating fermionic dark matter (DM)."

The fermionic matter explanation says the DM can account for stellar motion the same way an SMBH can. The DM adheres to a dense core–diluted halo morphology, so it explains both the S-stars and the galaxy's rotation curve, as revealed by Gaia. Convincingly, it can also account for the shadow-like features in the EHT image of Sagittarius A-star.

The authors say that the fermion dark matter explanation "can also produce shadow-like features with sizes compatible with the measurements of the EHT collaboration when applied to Milky Way-like galaxies."

*This is the well-known Event Horizon Telescope image of the Milky Way's Galactic Core. It was the first visual evidence that the MW hosted a SMBH. It doesn't directly show a black hole because they' can't be seen. But it shows orbiting glowing gas and a dark central region called the shadow. Image Credit: By EHT Collaboration - https://www.eso.org/public/images/eso2208-eht-mwa/ (image link), CC BY 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=117933557*

*This is the well-known Event Horizon Telescope image of the Milky Way's Galactic Core. It was the first visual evidence that the MW hosted a SMBH. It doesn't directly show a black hole because they' can't be seen. But it shows orbiting glowing gas and a dark central region called the shadow. Image Credit: By EHT Collaboration - https://www.eso.org/public/images/eso2208-eht-mwa/ (image link), CC BY 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=117933557*

So, what is fermionic dark matter?

Fermions are basically light subatomic particles. Some are elementary particles like quarks and leptons, and some are composite particles. That includes all baryons, as well as some atoms and atomic nuclei. Composite fermions also include protons and neutrons, the basic building blocks of regular matter.

The basic idea is that fermions obey the Pauli exclusion principle. That means they can't collapse into a singularity, but can still create a dense enough object with enough gravity to explain S-stars, G-clouds, and other evidence usually cited to support the SMBH hypothesis.

The authors propose that dark fermions don't interact electromagnetically. Instead, like dark matter, they only interact gravitationally. Dark fermions are the same type of particle used to explain dark matter haloes around galaxies, and the researchers say that under the right conditions, they could collapse into extremely dense concentrations in galactic centers. These collapsed concentrations of dark matter fermions could mimic what we think are SMBH.

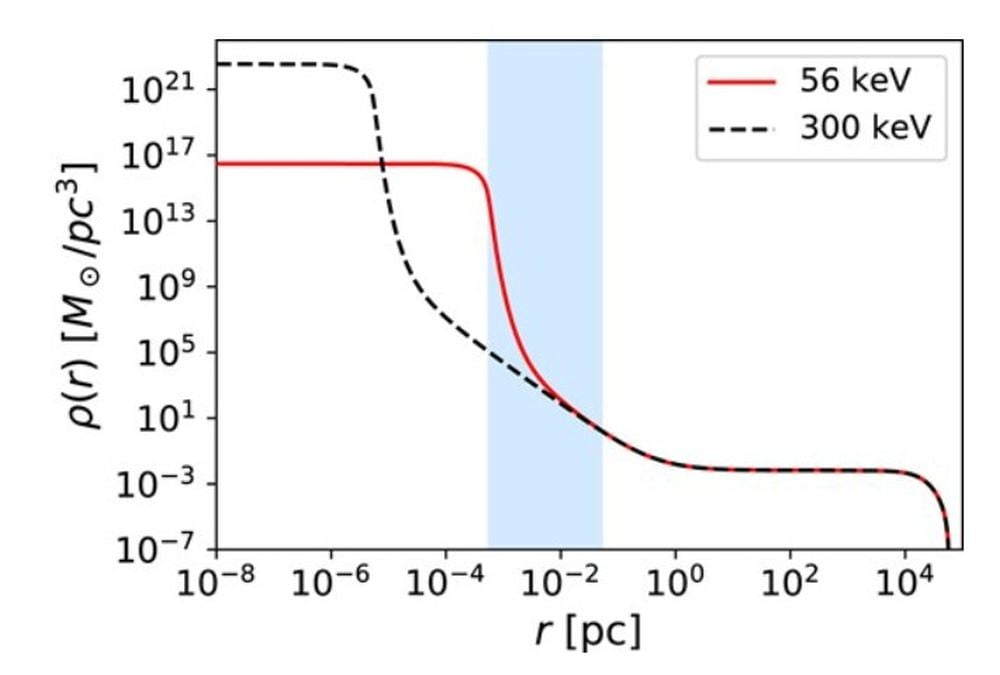

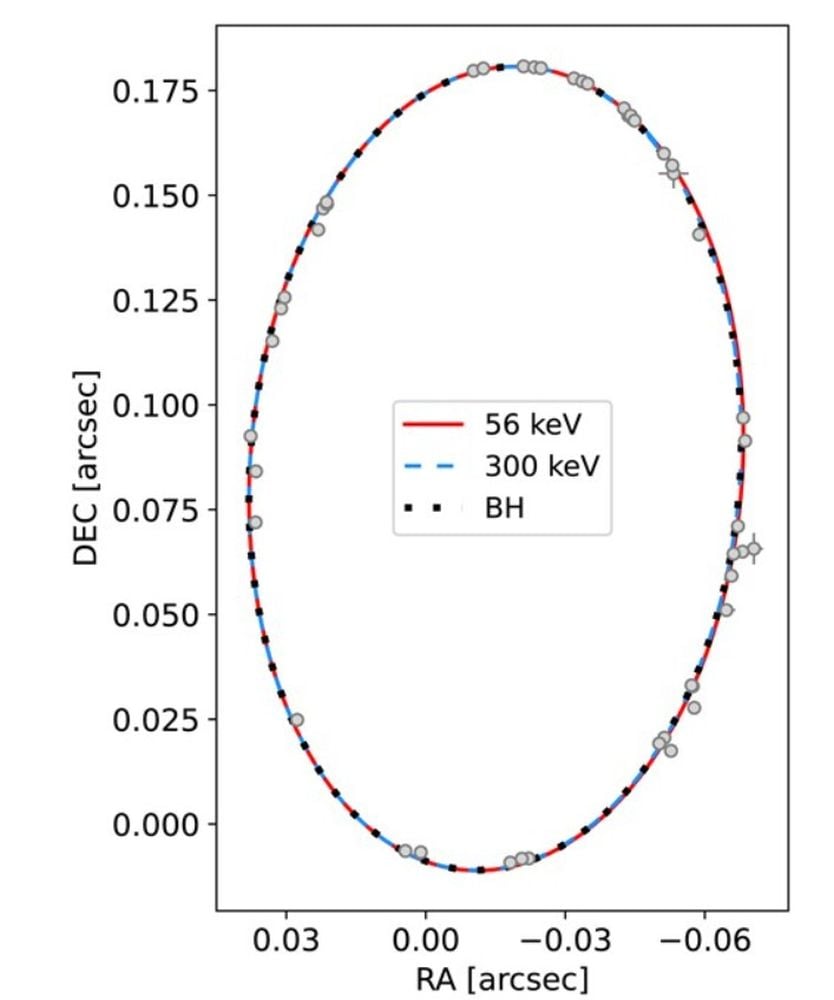

In their work, the researchers tested two different fermions: 56 keV and 300 keV. The 56 keV fermions create a less compact core, while the 300 keV fermions create a more compact core. Both models can create the S-star and G-cloud orbits. Their orbital parameters differed by less than only one percent compared to black hole models.

*This figure shows the energy density profiles for both types of dark fermions tested in the research. The blue band shows the locations of the most relevant S-stars and G-objects. The figure shows that both types of hypothesized dark fermions can explain both S-stars and G-objects. Image Credit: Crespi et al. 2026. MNRAS*

*This figure shows the energy density profiles for both types of dark fermions tested in the research. The blue band shows the locations of the most relevant S-stars and G-objects. The figure shows that both types of hypothesized dark fermions can explain both S-stars and G-objects. Image Credit: Crespi et al. 2026. MNRAS*

The work shows that the dark fermions can create a super-dense and compact core surrounded by a more diffuse halo.

"This is the first time a dark matter model has successfully bridged these vastly different scales and various object orbits, including modern rotation curve and central stars data," said study co-author Dr Carlos Argüelles, of the Institute of Astrophysics La Plata. "We are not just replacing the black hole with a dark object; we are proposing that the supermassive central object and the galaxy's dark matter halo are two manifestations of the same, continuous substance."

There's plenty of evidence that the Milky Way has a dark matter halo. The halo can explain the galactic rotation curve, stellar velocities in the outer Milky Way and its nearby satellite galaxies, and the motion of the satellite galaxies. This research links the DM halo to the dense core as one, continuous object.

This isn't the first research effort showing that dark matter cores can take the place of SMBH. A 2024 paper published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society showed that these dark matter cores can also cast shadow-like features seen in the EHT image of the Milky Way's core. "We have obtained image features similar to those expected in the BH case of the same mass as the DM core, with the central brightness depression and surrounding ring-like structure being the most relevant," those authors explained.

"This is a pivotal point," said lead author Crespi in a press release. "Our model not only explains the orbits of stars and the galaxy's rotation but is also consistent with the famous 'black hole shadow' image. The dense dark matter core can mimic the shadow because it bends light so strongly, creating a central darkness surrounded by a bright ring."

The authors point out that although there dark fermion model is plausible, it's a long way from being proven. Since the differences between S-star orbits in the SMBH model and the dark fermion model are less than one percent, only more accurate observations can distinguish between them.

*This figure shows the orbit of the S2 star. There's very little difference between the star's observed orbit (BH, black) and the two modelled orbits from the two types of dark fermions. Image Credit: Crespi et al. 2026. MNRAS*

*This figure shows the orbit of the S2 star. There's very little difference between the star's observed orbit (BH, black) and the two modelled orbits from the two types of dark fermions. Image Credit: Crespi et al. 2026. MNRAS*

There's also the issue of photon rings, also called photon spheres. General relativity says that near a black hole's event horizon, photons can display boomerang-like motion as their trajectories are bent by gravity. Since they're an artifact of a singularity, they won't be present near a dark matter fermion core. One group of researchers claimed to have imaged a photon ring around Sagittarius A-star, but that claim was heavily criticized by other scientists.

If this hypothesis turns out to be true, then we're in another one of those "re-write the textbook" moments. Only better data and measurements can get us there.

"All in all, we conclude that it is necessary to have a better quality and quantity of data to differentiate between the BH and fermionic models," the authors explain. "In addition, accurate enough data from stars orbiting inside the S2 orbit is crucial, given it tests stronger gravitational potentials in the surroundings of Sgr A*."